Architecture and Layout

Without a doubt, the ancient Egyptian architects were far more advanced than anyone could have imagined. Using the natural caverns within the valley, ancient architects carved walls, chambers and intricate pathways without any modern tools with surprising precision. Egyptians tools such as picks, hammers, shovels and chisels were made of wood, stone, ivory, bone and copper.

Although impressive, the architecture and layout of the Valley’s earliest burial tombs are inconsistent.

There are no unified patterns of the tombs’ layouts. Because of the unpredictability of limestone formations in the area, pharaohs invariably tried to choose what they perceived to be the more ‘superior’ spot, compared to their predecessors.

Later, the construction of large tombs became more ‘standardized’, with three corridors being followed by an antechamber and a ‘secure’, sometimes hidden, sunken sarcophagus chamber nestled in a very deep part of the tomb.

© Joonas Plaan – Tomb of Twosret in the Valley of the Kings

This was not ‘the’ standard design or layout of the axis of burial tombs for the Pharaohs. However, since some builders deviated from this unwritten rule, usually at the behest of the pharaoh who commissioned the tomb, sometimes more ‘fail-safes’ against robbery were added into tomb layouts.

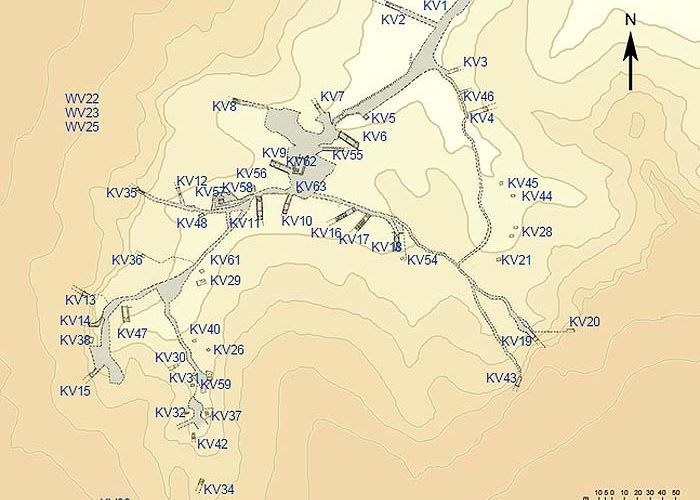

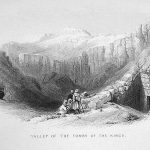

Tombs in the Valley of the Kings

Which ones of the pharaohs were interred first in the Valley of the Kings remains debated to this day, it is assumed by many scholars that it was either Amenhotep I, or Thutmose I. While the veracity of the former is still uncertain, extant historical records dating back to the period prove that it was Thutmose I, who was one of the first pharaohs interred in the Valley.

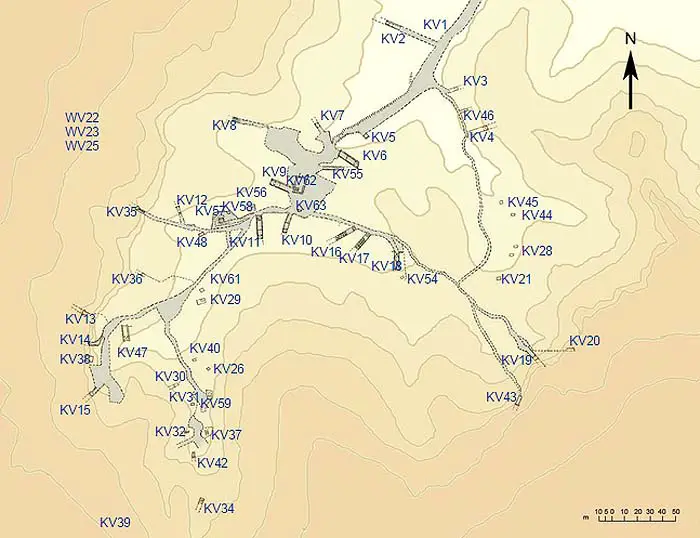

The East Valley holds a significantly larger number of tombs than the West, which has only four known tombs. The tombs are known by the order of discovery: the first tomb found was Ramses VII and was given the label of KV1, where KV stands for “Kings’ Valley”. Not all of the tombs were used to house bodies, some only held supplies, while others were completely empty.

Source: Wikipedia – Tombs in the Valley of the Kings

Tutankhamun

In the East Valley, in 1922, Howard Carter found what was labeled KV62: the tomb of Tutankhamun.

While many of the tombs and chambers in the area were sacked by thieves, this one was intact and stocked full with treasures. Valuable things as jewelry, statues, weapons and the Pharaoh’s chariot, were valuable finds, but the real treasure was the magnificently decorated sarcophagus, with the young king’s remains inside.

© Kačka a Ondra – Inner coffin of Tutankhamun

KV62 was the last large find until early 2006, when KV63 was excavated; KV64 was later found using radar technology. These recent discoveries are as fascinating as the ones found earlier in the 20th century, though KV64 has yet to be excavated itself.

New finds in the Valley of the Kings shows that KV63 is not a tomb, but a storage chamber, as none of the seven coffins hold mummies; instead, there are clay pots used in the mummification process. However, the information has not yet been verified by the Supreme Council of Antiquities, as the find was not properly presented before the Council before sending out news of the find.

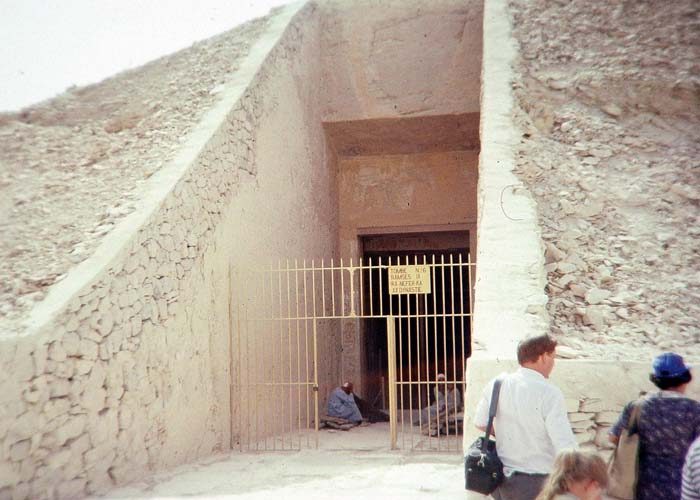

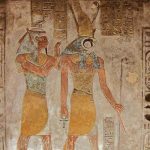

Ramses II

Unlike Tutankhamun, who died in his teens, another king survived much longer. Pharaoh Ramses II lived a full life and was also buried here.

Considered the greatest of all Egypt’s kings, his intention was to leave a legacy that would last forever. Grand statues of the Pharaoh were erected around Egypt’s great building projects like the Abu Simbel temples, for the purpose of distinguishing himself from other Pharaohs. As such, the tomb of Ramses II is nothing less than grand.

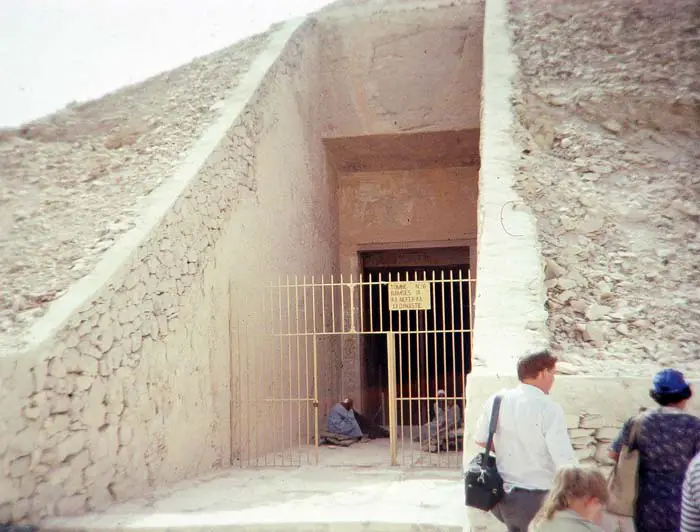

© Jimmy Smith – Entrance to the Tomb of Ramses II

It is one of the largest tombs in the Valley of the Kings, with a deep sloping entrance corridor, which leads to a grand pillared chamber. The corridors then break off into the well decorated burial chamber, and multiple side chambers. All of which are amazing feats of ancient engineering found in other larger tombs.

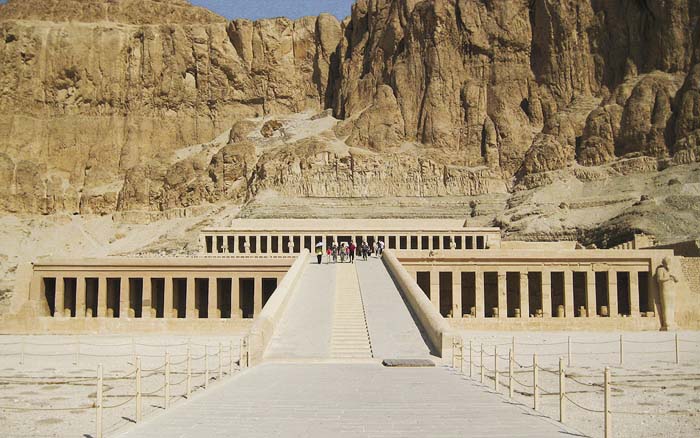

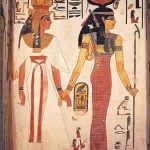

Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple

In the nearby area of Deir el-Bahri is a mortuary temple commissioned to be built by Hatshepsut, the first woman to take the title King of Upper and Lower Egypt, as no title existed for the female equivalent; the closest there came was Queen Consort, and this was not her role at all.

The mortuary temple was found by a local family to house a large number of mummies; the family would remove artifacts from a mummy or two and sell them, though this came to a halt in 1881 when authorities found out and were sent to investigate.

© Mohd Tarmizi – Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

The mummies of over 50 kings, queens, and assorted nobles were moved from the Valley of the Kings to this temple by priests during the 21st Dynasty to preserve them from looting and desecration by grave robbers. Nearby, another cache was found holding the mummies of the priests that had moved the pharaohs to begin with.