Evidence about dress becomes plentiful only after humans began to live together in greater numbers in discrete localities with well-defined social organizations, with refinements in art and culture, and with a written language. This happened first in the ancient world in Mesopotamia (home of the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians) and in Egypt. Later other parts of the Mediterranean region were home to the Minoans (on the island of Crete), the Greeks, the Etruscans, and the Romans (on the Italian peninsula).

The sociocultural phenomenon called “fashion,” that is, styles being widely adopted for a limited period of time, was not part of dress in the ancient world. Specific styles differed from one culture to another. Within a culture some changes took place over time, but those changes usually occurred slowly, over hundreds of years. In these civilizations tradition, not novelty, was the norm.

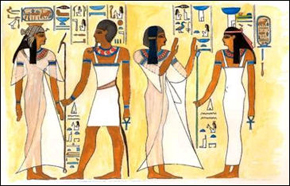

Certain common forms, structure, and elements appear in the dress of the different civilizations of the ancient world. Costume historians differentiate between draped and tailored dress. Draped clothing is made from lengths of fabric that are wrapped around the body and require little or no sewing. Tailored costume is cut into shaped pieces and sewn together. Draped costume utilizes lengths of woven textiles and predominates in warm climates where a loose fit is more comfortable. Tailored costume is thought to have originated around the time when animal skins were used. Being smaller in size than woven textiles, skins had to be sewn together. Tailored garments, cut to fit the body more closely, are more common in cold climates where the closer fit keeps the wearer warm. With a few exceptions, ancient world garments of the Mediterranean region were draped.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Evidence About Dress

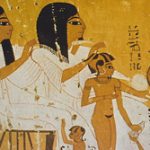

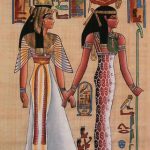

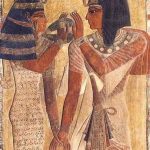

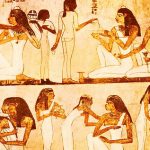

Most of the evidence about costume of the ancient world comes from depictions of people in the art of the time. Often this evidence is fragmentary and difficult to decipher because researchers may not know enough about the context from which items come or about the conventions to which artists had to conform.

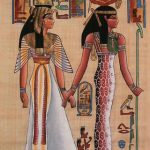

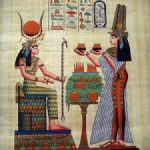

The geography and climate of a particular civilization and its religious practices may enhance or detract from the quantity and quality of evidence. Fortunately, the dry desert climate of ancient Egypt coupled with the religious beliefs that caused Egyptians to bury many different items in tombs have yielded actual examples of textiles and some garments and accessories.

Written records from these ancient civilizations may also contribute to what is known about dress. Such records are often of limited usefulness because they use terminology that is unclear today. They may, however, shed light on cultural norms or attitudes and values individuals hold about aspects of dress such as its ability to show status or reveal personal idiosyncrasies.

Common Types of Garments

Although they were used in unique ways, certain basic garment types appeared in a number of the ancient civilizations. In describing these garments, which had different names in different locales, the modern term that most closely approximates the garment will be used here. Although local practices varied, both men and women often wore the same garment types. These were skirts of various lengths; shawls, or lengths of woven fabric of different sizes and shapes that could be draped or wrapped around the body; and tunics, T-shaped garments similar to a loose-fitting modern T-shirt, that were made of woven fabric in varying lengths. E. J. W. Barber (1994) suggests that the Latin word tunica derives from the Middle Eastern word for linen and she believes that the tunic originated as a linen undergarment worn to protect the skin against the harsh, itchy feel of wool. Later tunics were also used as outerwear and were made from fabrics of any available fibers.

The primary undergarment was a loincloth. In one form or another this garment seems to have been worn in most ancient world cultures. It appears not only on men, but also is sometimes depicted as worn by women. It generally wrapped much like a baby’s diaper, and if climate permitted workers often used it as their sole out-door garment.

In most of the ancient world, the most common foot covering was the sandal. Occasionally closed shoes and protective boots are depicted on horsemen. A shoe with an upward curve of the toe appears in many ancient world cultures. This style seems to make its first appearance in Mesopotamia around 2600 B.C.E. and it is thought that it probably originated in mountainous regions where it provided more protection from the cold than sandals. Its depiction on kings indicates that it was associated with royalty in Mesopotamia. It probably came to be a mark of status elsewhere, as well (Born). Similar styles show up among the Minoans and Etruscans.

Mesopotamian Dress

The Sumerians, as the earliest settlers in the land around the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in what is now modern Iraq, established the first cities in the region. Active from about 3500 B.C.E. to 2500 B.C.E., they were supplanted as the dominant culture by the Babylonians (2500 B.C.E. to 1000 B.C.E.) who in turn gave way to the Assyrians (1000 B.C.E. to 600 B.C.E.).

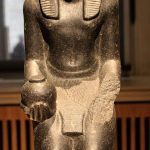

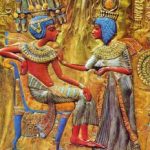

One of the chief products of Mesopotamia, wool, was used not only domestically but was also exported. Although flax was available, it was clearly less important than wool. The importance of sheep to clothing and the economy is reflected in representations of dress. Sumerian devotional or votive figures often depict men or women wearing skirts that appear to be made from sheepskin with the fleece still attached. When the length of material was sufficient, it was thrown up and over the left shoulder and the right shoulder was left bare.

Other figures seem to be wearing fabrics with tufts of wool attached, which were made to simulate sheepskin. The Greek word kaunakes has been applied to both sheepskin and woven garments of this type.

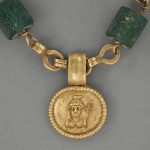

Additional evidence of the importance of wool fabric comes from archaeology. An excavation of the tomb of a queen from Ur (c. 2600 B.C.E.) included fragments of bright red wool fabric thought to be from the queen’s garments.

Evidence About Dress

Evidence for costume in this region comes from depictions of humans on engraved seals, devotional, or votive statuettes of worshipers, a few wall paintings, and statues and relief carvings of military and political leaders. Representations of women are few, and the writings from legal and other documents confirm the impression that women’s roles were somewhat restricted.

Major Costume Forms

In addition to the aforementioned kaunakes garment, early Sumerian art also depicts cloaks (capelike coverings). Costumes of later periods appear to have grown more complex, with shawls covering the upper body. Skirts, loincloths, and tunics also appear. A draped garment, probably made from a square of fabric 118 inches wide and 56 inches long (Houston 2002), appears on noble and mythical male figures from Sumer and Babylonia. Because the garment is represented as smooth, without folds or drapery, most scholars believe that this unlikely perfection was an artistic convention, not a realistic view of clothing. With this garment men wore a close-fitting head covering with a small brim or padded roll.

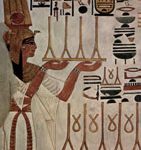

Women’s dress of this period covered the entire upper body. The most likely forms were a skirt worn with a cape that had an opening for the head or a tunic. Other wrapped and draped styles have also been suggested.

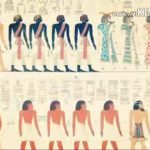

Transitions from Babylonian to Assyrian rule are not marked by clear changes in style. In time, the Assyrians came to prefer tunics to the skirts and cape styles that were more common in earlier periods. The length of tunics varied with the gender, status, and occupation of the wearer. Women’s tunics were full-length, as were those of kings and highly placed courtiers. Common people and soldiers wore short tunics.

Fabrics ornamented with complex designs appeared in Assyria. Scholars are uncertain whether the designs on royal costumes are embroidered or woven. Elaborate shawls were wrapped over tunics, and the overall effect was complex and multilayered. Priests selected the most favorable colors and garments for the ruler to wear on any given day.

Hairstyles and headdress are important elements of dress and often convey status, occupation, or relate to other aspects of culture. Sumerian men are depicted both clean-shaven and bearded. Sometimes they are bald. In hot climates shaving the head may be a health measure and done for comfort. Both men and women are also shown with long, curly hair, which is probably an ethnic characteristic. Assyrian men are bearded and have such elaborately arranged curls that curling irons may have been used. In art women’s hair is shown as either ornately curled or dressed simply at about shoulder length.

The status of women apparently changed over time. From laws it is clear that Sumerian and Babylonian women had more legal protections than did Assyrian women. Law codes make reference to veiling and it appears that in Sumerian and Babylonian periods, free married women wore veils, while slaves and concubines were permitted to wear veils only when accompanied by the principal wife. Specific practices as to how and when the veil was worn are not entirely clear; however, it is evident that traditions surrounding the wearing of veils by women have deep roots in the Middle East.