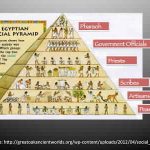

After a person died, their remains were transported to the embalmers’ premises. Here three levels of service were available. For the wealthy was the best and therefore the most expensive service. Egypt’s middle classes could take advantage of a more affordable option, while the working class could probably only afford the lowest level embalming available.

Naturally, a pharaoh received the most elaborate embalming treatment producing the best-preserved bodies and elaborate burial rituals.

If a family could afford the most expensive form of embalming yet opted for a cheaper service they risked being haunted by their deceased. The belief was that the deceased would know they had been given a cheaper embalming service than they deserved. This would prevent them from peacefully journeying into the afterlife. Instead, they would return to haunt their relatives, making their lives miserable until the wrong perpetrated against the deceased had been corrected.

The Mummification Process

Burial of the deceased involved making four decisions. Firstly, the level of embalming service was selected. Next, a coffin was chosen. Thirdly came the decision on how elaborate the funerary rites performed at and following the burial were going to be and finally, how the body was to be treated during its preparation for burial.

The key ingredient in the ancient Egyptian’s mummification process was natron or divine salt. Natron is a mixture of sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride and sodium sulphate. It occurs naturally in Egypt particularly in Wadi Natrun sixty-four kilometres northwest of Cairo. It was Egyptians’ preferred desiccant thanks to its de-fatting and desiccating properties. Common salt was also substituted in cheaper embalming services.

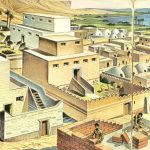

Ritual mummification started four days after the deceased’s death. The family moved the body to a location on the west bank of the Nile.

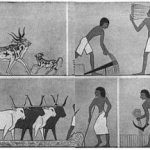

For the most expensive form of embalming, the body was laid on a table and thoroughly washed. The embalmers then removed the brain using an iron hook via the nostril. The skull was then rinsed out. Next, the abdomen was opened using a flint knife and the contents of the abdomen were removed.

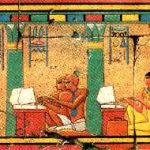

Towards the beginning of Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty, embalmers began removing and preserving the major organs. These organs were deposited in four Canopic jars filled with a solution of natron. Typically these Canopic jars were carved from, alabaster or limestone and featured lids shaped in a likeness of Horus’ four sons. The sons, Duamutef, and Imsety, Qebhsenuef and Hapy stood guard over the organs and a set of jars usually featured heads of the four gods.

The empty cavity was then cleaned thoroughly and rinsed out, firstly using palm wine and then with an infusion of ground spices. After being treated, the body was filled with a mix of pure cassia, myrrh and other aromatics before being sewn up.

At this point in the process, the body was immersed in natron and covered entirely. It was then left for between forty and seventy days to dry out. Following this interval, the body was washed once more before being wrapped from head to toe in linen cut into broad strips. It could require up to 30 days to finish with the wrapping process, preparing the body for burial. The linen strips were smeared on the underside with gum.

The embalmed body was then returned to the family for internment in a wooden human shaped casket. The embalming tools were frequently buried in front of the tomb.

In 21st Dynasty burial, embalmers attempted to make the body look more natural and less desiccated. They stuffed the cheeks with linen to make the face appear fuller. Embalmers also experimented with a subcutaneous injection of a mixture of soda and fat.

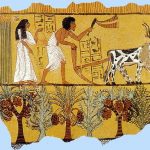

This embalming process was followed for animals too. Egyptians regularly mummified thousands of sacred animals together with their pet cats, dogs, baboons, birds, gazelles and even fish. The Apis bull viewed as an incarnation of the divine was also mummified.

The Role Of Tombs In Egyptian Religious Beliefs

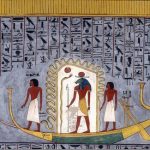

Tombs were not viewed as a deceased’s final resting place but as the body’s eternal home. The tomb was now where the soul left the body to journey on through the afterlife. This contributed to the belief that the body must remain intact if the soul was to successfully journey onwards.

Once freed from the constraints of its body, the soul needs to draw upon objects that had been familiar in life. Hence tombs were often elaborately painted.

To the ancient Egyptians, death was not the end but merely a transition from one form of existence to another. Thus, the body needed to be ritually prepared so the soul would recognise it upon reawakening each night in its tomb.

Reflecting On The Past

Ancient Egyptians believed that death was not the end of life. The deceased could still see and hear. If wronged, would be given leave by the gods to exact their horrible revenge upon their relatives. This social pressure emphasized treating the dead with respect and providing them with embalming and funeral rites, which befitted their status and means.