Cults were sects dedicated to serving one deity. From the Old Kingdom onwards, priests were usually the same sex as their god or goddess. Priests and priestesses were allowed to marry, to have children and to own property and land. Aside from ritual observances requiring purification prior to officiating at rites, priests and priestesses lived regular lives.

Members of the priesthood underwent an extended period of training prior to officiating at a ritual. The cult members maintained their temple and its surrounding complex, performed religious observances and sacred rituals including marriages, blessing a field or home and funerals. Many acted as healers, and doctors, calling upon the god Heka as well as scientists, astrologers, marriage counsellors and interpreted dreams and omens. Priestesses serving the goddess Serkey provided medical care doctors but it was Heka who provided the power to invoke Serket to heal their petitioners.

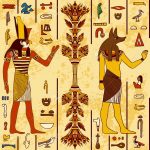

Temple priests blessed amulets to encourage fertility or to protect against evil. They also performed purification rites and exorcisms to rid expel evil forces and ghosts. A cult’s primary charge was to serve their god and their followers amongst their local community and to care for the statue of their god inside their temple.

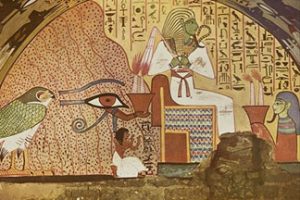

Ancient Egypt’s temples were believed to be the actual earthly homes of their gods and goddesses. Each morning, a head priest or priestess would purify themselves, dress in the fresh white linen and clean sandals signifying their office before going into the heart of their temple to tending to their god’s statue as they would anyone placed in their care.

The temple doors were opened to flood the chamber with morning sunlight before the statue in the innermost sanctuary was cleansed, re-dressed and bathed in fragrant oil. Afterwards, the doors to the inner sanctuary were closed and secured. The head priest alone enjoyed close proximity to the god or goddess. Followers were restricted to the temple’s outer areas for worship or to have their needs addressed by lower-level priests who also accepted their offerings.

Temples gradually amassed social and political power, which rivalled that of the pharaoh himself. They owned farmland, securing their own food supply and received a share in the booty from the pharaoh’s military campaigns. It was also common for Pharaohs to gift land and goods to a temple or to pay for its renovation and extension.

Some of the most expansive temple complexes were located at Luxor, at Abu Simbel, the Temple of Amun at Karnak, and the Temple of Horus at Edfu, Kom Ombo and Philae’s Temple of Isis.

Religious Texts

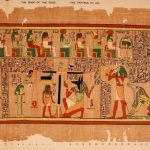

Ancient Egyptian religious cults did not have codified standardized “scriptures” as we know them. However, Egyptologists believe the core religious precepts invoked at the temple approximated those outlined in the Pyramid Texts, The Coffin Texts and the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

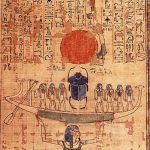

The Pyramid Texts remain ancient Egypt’s oldest sacred passages and date from c. 2400 to 2300 BCE. The Coffin Texts are believed to have come after the Pyramid Texts and date to around c. 2134-2040 BCE, while the famed Book of the Dead known to ancient Egyptians as the Book on Coming Forth by Day is thought to have been first written sometime between c.1550 and 1070 BCE. The Book is a collection of spells for the soul to use to aid its passage through the afterlife. All three works contain detailed instruction to assist the soul in navigating the many perils awaiting it in the afterlife.

The Role of Religious Festivals

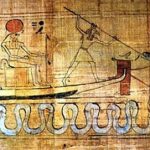

Egypt’s sacred festivals blended the sacred nature of honouring the gods with the everyday secular lives of the Egyptian people. Religious festivals mobilised worshippers. Elaborate festivals like The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi a celebrated life, community and wholeness honouring of the god Amun. The god statue would be taken from its inner sanctuary and carried on a ship or in an ark into the streets parading around households in the community to participate in the celebrations before being launched onto the Nile. Afterwards, priests answered petitioners while oracles revealed the will of the gods.

Worshippers attending the Festival of the Wadi visited Amun’s shrine to pray for physical vitality and left votive offerings for their god in gratitude for their health and their lives. Many votives were offered intact to the god. On other occasions, they were ritually smashed to underline worshipper’s devotion to their god.

Entire families attended these festivals, as did those looking for a partner, younger couples and teenagers. Older community members, the poor as well as the rich, the nobility and slaves all partook in the community’s religious life.

Their religious practices and their day-to-day lives intermingled to create ancient Egypt’s social framework based on harmony and balance. Within this framework, an individual’s life was interconnected to the health of society as a while.

The Wepet Renpet or “Opening of the Year” was an annual celebration held to mark the start of a new year. The festival ensured fertility of the fields for the coming year. Its date varied, as it was associated with the Nile’s annual floods but usually took place in July.

The Festival of Khoiak honoured Osiris’ death and resurrection. When the Nile River’s floods eventually receded, Egyptians planted seeds in Osiris beds to ensure their crops would flourish, just as Osiris reputedly had.

The Sed Festival honoured the Pharaoh’s kingship. Held every third year during a Pharaoh’s reign, the festival was rich in ritual rites, including making an offering of the spine of a bull, representing the pharaoh’s vigorous strength.

Reflecting On The Past

For 3,000 years, ancient Egypt’s rich and complex set of religious beliefs and practices endured and evolved. Its emphasis on leading a good life and on an individual’s contribution to harmony and balance across society as a whole illustrates how effective the lure of a smooth passage through the afterlife was for many ordinary Egyptians