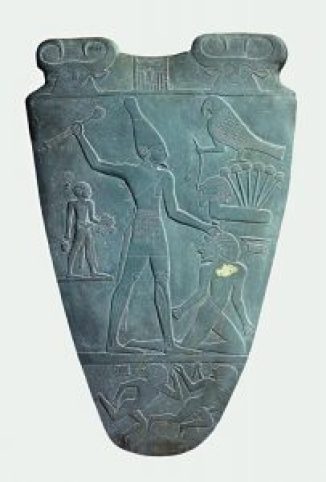

The Narmer Palette, an ancient Egyptiancermonial engraving, depicts the great king Narmer (c. 3150 BCE) conquering his enemies with the support and approval of his gods. This piece, dating from c. 3200-3000 BCE, was initially thought to be an accurate historical depiction of the unification of Egypt under Narmer, the first king of the First Dynasty. Recent revisions in scholarship, however, now interpret the artifact as a symbolic rendering of this historical event and claim that Narmer (also known as Menes) may or may not have united the country by force but that the concept of the king as a mighty warrior was an important cultural value and so Narmer was depicted as a conqueror.

The great kings of Mesopotamia, especially the Assyrian rulers, left behind many inscriptions of their military victories, prisoners taken, cities destroyed but for most of Egypt’s early history such records do not exist. The Egyptians considered their land the most perfect in the world and were not so much interested in conquest as in preservation of what they had. The early records of Egyptian warfare all have to do with civil unrest, not conquest of other lands, and this would be the paradigm from the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-2613 BCE) until the time of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) when the kings of the 12th Dynasty maintained a standing army which they led on military campaigns beyond their borders.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF PROFESSIONAL WARFARE

Although modern day scholars disagree on whether Narmer united Egypt through conquest, there is no doubt that a military force under a strong leader was necessary to hold the country together. Throughout the First Dynastic Period there is evidence of unrest, perhaps even a division of the country at one point, and civil wars between factions fighting for the throne.

DURING THE NEW KINGDOM PERIOD EGYPT EXPANDED ITS EMPIRE & WAS CONSTANTLY AT WAR. THUTHMOSE III LED AT LEAST SEVENTEEN DIFFERENT CAMPAIGNS IN TWENTY YEARS.

Through the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) the central government relied on regional governors (nomarchs) to supply men for the army. The nomarch would conscript soldiers in their region and send them to the king. Each battalion carried standards bearing the totem of their district (nome) and their loyalties were with their community, their brothers-in-arms, and to their nomarch. The effectiveness of this early militia is attested to by the successful campaigns in Nubia, Syria, and Palestine of Old Kingdom monarchs to either secure the borders, quell uprisings, or seize resources for the crown. The soldiers fought for the king and their country but they were not a united Egyptian army so much as a band of smaller military units fighting for a common goal. The conscripts were often supplemented by Nubian mercenaries who had the same degree of loyalty to the king as long as they were being paid.

The rise in the power of individual nomarchs was among the contributing factors in the collapse of the Old Kingdom and the beginning of the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181-2040 BCE). The central government at Memphis was no longer relevant as each district’s nomarch assumed control of their own region, built temples in their own honor instead of a king’s, and used their militia for their own ends. In an attempt to regain some of their lost prestige, perhaps, the kings at Memphis moved their capital to the city of Herakleopolis, which was more centrally located. They were no more effective at the new location, however, than they had been at the old and were overthrown by Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) of Thebes who initiated the period of the Middle Kingdom.

It is likely that Mentuhotep II led an army of conscripts from Thebes but he may have already mobilized a professional fighting force in his district. It is also entirely possible that there was a core of professional soldiers who fought for the king as far back as the Pre-Dynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 BCE) but the evidence for this is unclear. Most scholars agree that it was Mentuhotep II’s successor, Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) who created the first standing army in Egypt. This would make a great deal of sense because it would have taken power from the individual nomarchs and placed it in the hands of the king. The king now had direct control of an army which was loyal to him and the country as a whole, not to different nomarchs and their regions.