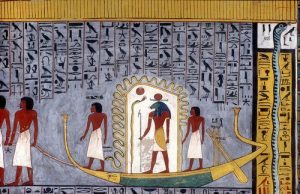

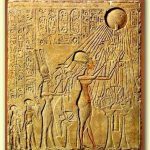

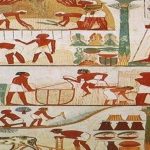

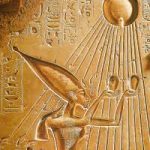

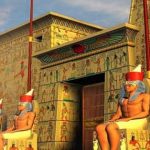

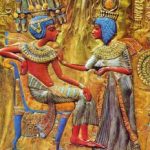

Religion in ancient Egypt was fully integrated into the people’s daily lives. The gods were present at one’s birth, throughout one’s life, in the transition from earthly life to the eternal, and continued their care for the soul in the afterlife of the Field of Reeds. The spiritual world was ever present in the physical world and this understanding was symbolized through images in art, architecture, in amulets, statuary, and the objects used by nobility and clergy in the performance of their duties.

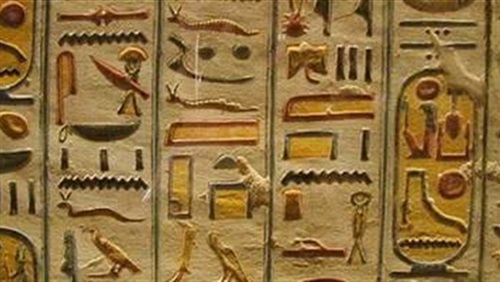

Symbols in a largely illiterate society serve the vital purpose of relaying the most important values of the culture to the people generation after generation, and so it was in ancient Egypt. The peasant farmer would not have been able to read the literature, poetry, or hymns which told the stories of his gods, kings, and history but could look at an obelisk or a relief on a temple wall and read them there through the symbols used.

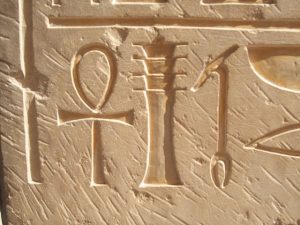

The three most important symbols, often appearing in all manner of Egyptian artwork from amulets to architecture, were the ankh, the djed, and the was scepter. These were frequently combined in inscriptions and often appear on sarcophagi together in a group or separately. In the case of each of these, the form represents the eternal value of the concept: the ankh represented life; the djed stability; the was power. Scholar Richard H. Wilkinson, noting the importance of form-as-function, relates the following:

A little known but fascinating inscription made at the command of the pharaohThutmose IV records the discovery by the king of a stone. The significance of this celebrated stone lay not in its being of rare material or appearance, the inscription tells us, but because “his majesty found this stone in the shape of a divine hawk”. That an Egyptian king should place so much importance on a mere rock simply because of its shape is instructive, for it shows how alert the ancient Egyptian was to the shapes of objects and to the symbolic importance which the dimension of form could hold. (16)

The Ankh

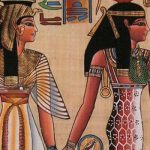

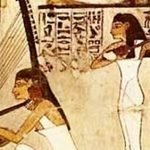

The ankh is a cross with a looped top which, besides the concept of life, also symbolized eternal life, the morning sun, the male and female principles, the heavens and the earth. Its form embodied these concepts in its key-like shape; in carrying the ankh, one was holding the key to the secrets of existence. The union of opposites (male and female, earth and heaven) and the extension of earthly life to eternal, time to eternity, were all represented in the form of the looped cross. The symbol was so potent, and so long-lived in Egyptian culture (dating from the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt, c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE), that it is no surprise it was appropriated by the Christian faith in the 4th century CE as a symbol for their god.

The origin of the ankh symbol is unknown, but Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge claims it may have developed from the tjet, the ‘Knot of Isis,’ a similar symbol with the arms at its sides associated with the goddess. Female deities were as popular, and seem to be considered more powerful (as in the example of the goddess Neith), in the early history of Egypt, and perhaps the ankh did develop from the tjet, but this theory is not universally accepted.

The ankh was closely associated with the cult of Isis, however, and as her popularity grew, so did that of the symbol. Many different gods are depicted holding the ankh and it appears, along with the djed symbol, in virtually every kind of Egyptian artwork from sarcophagi to tomb paintings, palace adornments, statuary, and inscriptions. As an amulet, the ankh was almost as popular as the scarab and the djed.

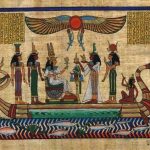

The Djed

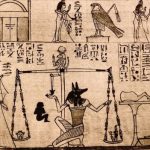

The djed is a column with a broad base narrowing as it rises to a capital and crossed by four parallel lines. It first appears in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000-c. 3150 BCE) and remains a staple of Egyptian iconography through the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE), the last to rule the country before the coming of Rome. Although understood as representing stability, the symbol served to remind one of the close presence of the gods as it also referenced the god Osiris and so was linked with resurrection and eternal life. The djed was thought to represent the god’s backbone and frequently appears on the bottom of sarcophagi in order to help the newly arrived soul stand up and walk into the afterlife.

The symbol has also been interpreted as four columns rising behind each other, the tamarisk tree in which Osiris is enclosed in his most popular myth, and a fertility pole raised during festivals, but in each case, the message of the form goes back to the stability in life and hope in the afterlife, provided by the gods.

In the interpretation of the symbol as four columns, the number most frequently appearing in Egyptian iconography is represented: four. The number symbolized completeness and is seen in art, architecture, and funerary goods such as the Four Sons of Horus of the canopic jars, the four sides of a pyramid, and so on. The other interpretations likewise symbolize concepts associated with the Osiris-Isis myth. The djed as the tamarisk tree speaks of rebirth and resurrection as, in the myth, the tree holds Osiris until he is freed and brought back to life by Isis. The fertility pole is also associated with Osiris who caused the waters of the NileRiver to rise, fertilize the land, and flow again to its natural course. In each case, whatever object it is claimed to represent, the djed was a very powerful symbol which was often coupled with another: the was scepter.

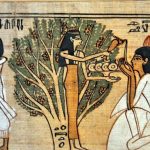

The Was Scepter

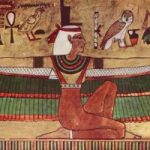

The was scepter is a staff topped with the head of a canine, possibly Anubis, by the time of the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) but earlier a totemic animal like a fox or dog. The wasscepter evolved from the earliest scepters, a symbol of royal power, known as the hekat, seen in representations of the first king, Narmer (c. 3150 BCE) of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-2613 BCE). By the time of the king Djet (c. 3000-2990 BCE) of the First Dynasty, the was scepter was fully developed and symbolized one’s dominion and power.

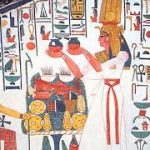

The scepter was usually forked at the bottom but this changed according to which god or mortal was holding it and so did the color of the staff. Hathor, associated with the cow, holds the scepter forked at the bottom in the shape of cow horns. Isis holds a similar object but with the traditional fork representing duality. The was scepter of Ra-Horakhty (‘Horus in the Horizon’), god of the rising and setting sun, was blue to symbolize the sky while that of the sun god Ra was represented with a snake attached to it symbolizing rebirth, as the sun rose again each morning.

Each god’s was scepter denoted their particular dominion in one way or another. The god Ptah, from the Early Dynastic Period, holds a was scepter which combines all three symbols, the ankh, djed, and was, with a circle at the bottom symbolizing unity. The combination of the symbols, naturally, combined their power which was only fitting for this god who was associated with creation and known as the ‘sculptor of the earth.’ The three symbols at the top of Ptah’s staff, along with the circle at the bottom, presented the overall meaning of completeness, totality, in the number four.