Marriage and the Family

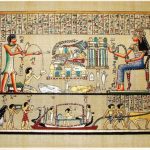

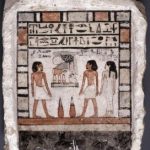

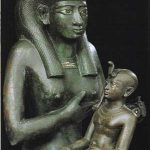

The nuclear family was the core of Egyptian society and many of the gods were even arranged into such groupings. There was tremendous pride in one’s family, and lineage was traced through both the mother’s and father’s lines. Respect for one’s parents was a cornerstone of morality, and the most fundamental duty of the eldest son (or occasionally daughter) was to care for his parents in their last days and to ensure that they received a proper burial.

Countless genealogical lists indicate how important family ties were, yet Egyptian kinship terms lacked specific words to identify blood relatives beyond the nuclear family. For example, the word used to designate “mother” was also used for “grandmother,” and the word for “father” was the same as “grandfather”; likewise, the terms for “son,” “grandson,” and “nephew” (or “daughter,” “granddaughter,” and “niece”) were identical. “Uncle” and “brother” (or “sister” and “aunt”) were also designated by the same word. To make matters even more confusing for modern scholars, the term “sister” was often used for “wife,” perhaps an indication of the strength of the bond between spouses.

Marriage

Once a young man was well into adolescence, it was appropriate for him to seek a partner and begin his own family. Females were probably thought to be ready for marriage after their first menses. The marrying age of males was probably a little older, perhaps 16 to 20 years of age, because they had to become established and be able to support a family.

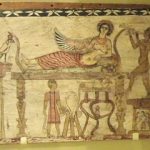

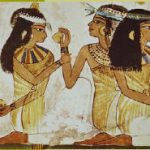

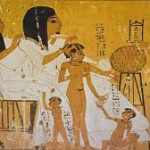

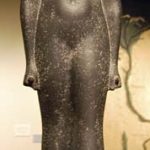

Virginity was not a necessity for marriage; indeed, premarital sex, or any sex between unmarried people, was socially acceptable. Once married, however, couples were expected to be sexually faithful to each other. Egyptians (except the king) were, in theory, monogamous, and many records indicate that couples expressed true affection for each other. They were highly sensual people, and a major theme of their religion was fertility and procreation. This sensuality is reflected by two New Kingdom love poems: “Your hand is in my hand, my body trembles with joy, my heart is exalted because we walk together,” and “She is more beautiful than any other girl, she is like a star rising . . . with beautiful eyes for looking and sweet lips for kissing” (after Lichtheim 1976: 182).

Marriage was purely a social arrangement that regulated property. Neither religious nor state doctrines entered into the marriage and, unlike other documents that related to economic matters (such as the so-called “marriage contracts”), marriages themselves were not registered. Apparently once a couple started living together, they were acknowledged to be married. As related in the story of Setne, “I was taken as a wife to the house of Naneferkaptah [that night , and pharaoh] sent me a present of silver and gold . . . He [her husband] slept with me that night and found me pleasing. He slept with me again and again and we loved each other” (Lichtheim 1980: 128).

, and pharaoh] sent me a present of silver and gold . . . He [her husband] slept with me that night and found me pleasing. He slept with me again and again and we loved each other” (Lichtheim 1980: 128).

The ancient Egyptian terms for marriage (meni, “to moor [a boat],” and grg pr, “to found a house”) convey the sense that the arrangement was about property. Texts indicate that the groom often gave the bride’s family a gift, and he also gave his wife presents. Legal texts indicate that each spouse maintained control of the property that they brought to the marriage, while other property acquired during the union was jointly held. Ideally the new couple lived in their own house, but if that was impossible they would live with one of their parents. Considering the lack of effective contraceptives and the Egyptian’s traditional desire to have a large family, most women probably became pregnant shortly after marriage.

Divorce

Although the institution of marriage was taken seriously, divorce was not uncommon. Either partner could institute divorce for fault (adultery, inability to conceive, or abuse) or no fault (incompatibility). Divorce was, no doubt, a matter of disappointment but certainly not one of disgrace, and it was very common for divorced people to remarry.

Although in theory divorce was an easy matter, in reality it was probably an undertaking complicated enough to motivate couples to stay together, especially when property was involved. When a woman chose to divorce–if the divorce was uncontested–she could leave with what she had brought into the marriage plus a share (about one third to two thirds) of the marital joint property. One text (Ostracon Petrie 18), however, recounts the divorce of a woman who abandoned her sick husband, and in the resulting judgment she was forced to renounce all their joint property. If the husband left the marriage he was liable to a fine or payment of support (analogous to alimony), and in many cases he forfeited his share of the joint property.

Egyptian women had greater freedom of choice and more equality under social and civil law than their contemporaries in Mesopotamia or even the women of the later Greek and Roman civilizations. Her right to initiate divorce was one of the ways in which her full legal rights were manifested. Additionally, women could serve on juries, testify in trials, inherit real estate, and disinherit ungrateful children. It is interesting, however, that in contrast to modern Western societies, gender played an increasingly important role in determining female occupations in the upper classes than in the peasant and working classes. Women of the peasant class worked side by side with men in the fields; in higher levels of society, gender roles were more entrenched, and women were more likely to remain at home while their husbands plied their crafts or worked at civil jobs.

Through most of the Pharaonic Period, men and women inherited equally, and from each parent separately. The eldest son often, but not always, inherited his father’s job and position (whether in workshop or temple), but to him also fell the onerous and costly responsibility of his parents’ proper burial. Real estate generally was not divided among heirs but was held jointly by the family members. If a family member wished to leave property to a person other than the expected heirs, a document called an imeyt-per (“that which is in the house”) would ensure the wishes of the deceased.