Unless they were very poor, for ancient Egyptians a marriage typically was accompanied by a contract essentially similar to our current prenuptial agreements. This contract outlined the bride price, which was the amount payable by the family of the groom to the family of the bride in exchange for the honour of marrying the bride. It also laid out the compensation due to the wife should her husband subsequently divorce her.

The marriage contract similarly specified the goods the bride brought to their marriage and which items the bride could take with her should she and her husband divorce. Custody of any children was always awarded to the mother. The children accompanied the mother in the event of a divorce, irrespective of who initiated the divorce. Surviving examples of ancient Egyptian marriage contracts veered towards ensuring the ex-wife was looked after and was not left impoverished and impecunious.

The bride’s father usually drafted the marriage contract. It was formally signed with witnesses present. This marriage contract was binding and was often the sole document needed to establish the legality of a marriage in ancient Egypt.

Gender Roles In Egyptian Marriage

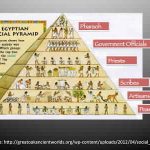

While men and women were largely equal under the law in ancient Egypt, there were gender-specific expectations. It was the obligation of the man in ancient Egyptian society to provide for his wife. When a man married, he was expected to bring to the marriage an established household. There was a strong social convention that men delayed marriage until they had sufficient means to support a household. Extended families rarely cohabited under the same roof. Establishing his own household showed a man was able to provide for a wife and any children that may they had.

The wife usually brought domestic items to the marriage depending on her family’s wealth and status.

An Absence Of Ceremony

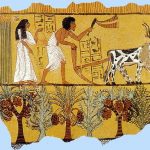

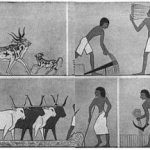

The ancient Egyptians valued the concept of marriage. Tomb paintings frequently show couples together. Moreover, archaeologists frequently found pair statues depicting the couple in tombs.

Despite these social conventions, which supported matrimony, the ancient Egyptians did not adopt a formal marriage ceremony as part of their legal process.

After the parents of a couple agreed on a union or the couples themselves decided to marry, they signed a marriage contract then the bride simply moved her belongings into her husband’s home. Once the bride had moved in, the couple were considered married.

Ancient Egypt And Divorce

Divorcing a partner in ancient Egypt was equally as straightforward as the marriage process itself. No complex legal processes were involved. The terms outlining the agreement in the event a marriage was dissolved were clearly detailed in the marriage contract, which surviving sources suggest were largely honoured.

During Egypt’s New Kingdom and Late Period, these marriage contracts evolved and became increasingly complex as divorce seems to have become increasingly codified and Egypt’s central authorities became more involved in divorce proceedings.

Many Egyptian marriage contracts stipulated that a divorced wife was entitled to spousal support until she remarried. Except where a woman inherited wealth, was typically responsible for his wife’s spousal support, regardless of whether children were part of the marriage or not. The wife also retained the dowry paid by the groom or the family of the groom prior to the wedding proceeding.

Ancient Egyptians And Infidelity

Stories and warnings about unfaithful wives are popular topics in ancient Egyptian literature. Tale of Two Brothers, known also as The Fate of an Unfaithful Wife was one of the most popular tales. It tells the story of the brothers Bata and Anpu and Anpu’s wife. The older brother, Anpu lived with his younger brother Bata and his wife. According to the story, one day, when Bata returned from working in the fields looking for more seed to sow, his brother’s wife tries to seduce him. Bata rejected her, promising not to tell anyone about what happened. He then went back to the fields. When Anpu returned home later his wife claimed Bata had attempted to rape her. These lies turn Anpu against Bata.

The story of the unfaithful woman emerged as a popular storyline due to the rich variation in potential outcomes infidelity could trigger. In the story of Anpu and Bata, their relationship between the two brothers is destroyed and the wife is ultimately killed. However, before her death, she causes problems in the brothers’ lives and within the broader community. The Egyptians’ strong stated belief in the ideal of harmony and balance on a social level would have generated significant interest in this storyline amongst ancient audiences.

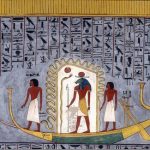

One of ancient Egypt’s most enduringly popular myths was that of the gods Osiris and Isis and Osiris’ murder at the hand of his brother Set. The story’s most widely copied version sees Set deciding to murder Osiris after his wife Nephthys’ decision to disguise herself as Isis in order to seduce Osiris. The chaos set in motion by Osiris’ murder; set in the context of an unfaithful wife’s action apparently had a powerful impact on ancient audiences. Osiris is seen as blameless in the story as he believed he was sleeping with his wife. As is common in similar morality tales, the blame is laid firmly at the feet of Nephthys the “other woman.”

This view of the danger that could be caused by a wife’s infidelity partially explains Egyptian society’s strong response to instances of infidelity. Social convention placed significant pressure on the wife to be faithful to their husbands. In some instances where the wife wasn’t faithful and it was proven, the wife could be executed, either by being burned at the stake or by stoning. In many instances, the fate of the wife was not in the hands of her husband. A court could overrule a husband wishes and order the wife to be executed.