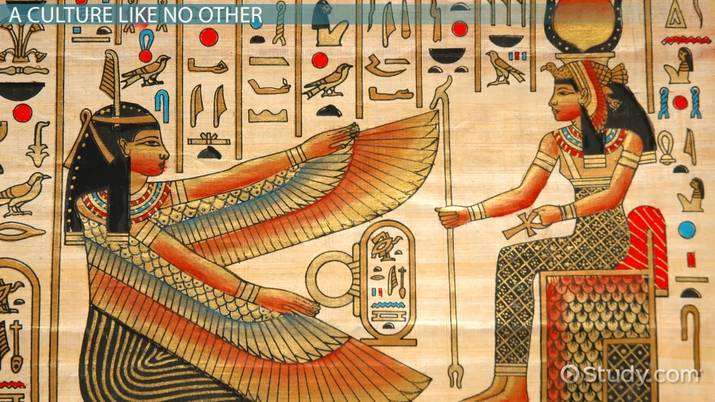

The artworks of ancient Egypt have fascinated people for thousands of years. The early Greek and later Roman artists were influenced by Egyptiantechniques and their art would inspire those of other cultures up to the present day. Many artists are known from later periods but those of Egypt are completely anonymous and for a very interesting reason: their art was functional and created for a practical purpose whereas later art was intended for aesthetic pleasure. Functional art is work-made-for-hire, belonging to the individual who commissioned it, while art created for pleasure – even if commissioned – allows for greater expression of the artist’s vision and so recognition of an individual artist.

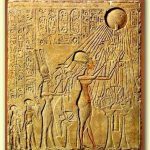

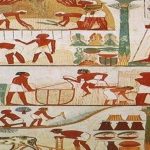

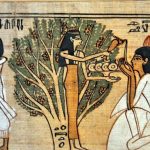

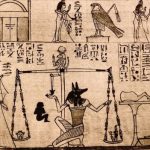

Greek artist like Phidias (c.490-430 BCE) certainly understood the practical purposes in creating a statue of Athena or Zeus but his primary aim would have been to make a visually pleasing piece, to make “art” as people understand that word today, not to create a practical and functional work. All Egyptian art served a practical purpose: a statue held the spirit of the god or the deceased; a tomb painting showed scenes from one’s life on earth so one’s spirit could remember it or scenes from the paradise one hoped to attain so one would know how to get there; charms and amulets protected one from harm; figurines warded off evil spirits and angry ghosts; hand mirrors, whip-handles, cosmetic cabinets all served practical purposes and ceramics were used for drinking, eating, and storage. Egyptologist Gay Robins notes:

As far as we know, the ancient Egyptians had no word that corresponded exactly to our abstract use of the word `art’. They had words for individual types of monuments that we today regard as examples of Egyptian art – ‘statue’, ‘stela’, ‘tomb’ -but there is no reason to believe that these words necessarily included an aesthetic dimension in their meaning.

(12)

Although Egyptian art is highly regarded today and continues to be a great draw for museums featuring exhibits, the ancient Egyptians themselves would never have thought of their work in this same way and certainly would find it strange to have these different types of works displayed out of context in a museum’s hall. Statuary was created and placed for a specific reason and the same is true for any other kind of art. The concept of “art for art’s sake” was unknown and, further, would have probably been incomprehensible to an ancient Egyptian who understood art as functional above all else.

Egyptian Symmetry

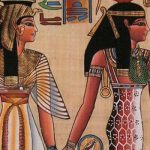

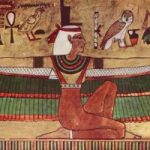

This is not to say the Egyptians had no sense of aesthetic beauty. Even Egyptian hieroglyphics were written with aesthetics in mind. A hieroglyphic sentence could be written left to right or right to left, up to down or down to up, depending entirely on how one’s choice affected the beauty of the finished work. Simply put, any work needed to be beautiful but the motivation to create was focused on a practical goal: function. Even so, Egyptian art is consistently admired for its beauty and this is because of the value ancient Egyptians placed on symmetry.

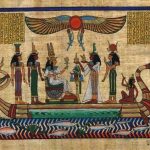

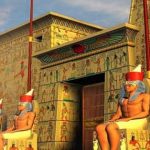

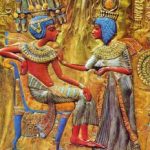

The perfect balance in Egyptian art reflects the cultural value of ma’at (harmony) which was central to the civilization. Ma’at was not only universal and social order but the very fabric of creation which came into being when the gods made the ordered universe out of undifferentiated chaos. The concept of unity, of oneness, was this “chaos” but the gods introduced duality – night and day, female and male, dark and light – and this duality was regulated by ma’at.

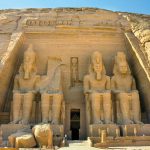

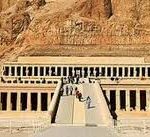

It is for this reason that Egyptian temples, palaces, homes and gardens, statuary and paintings, signet rings and amulets were all created with balance in mind and all reflect the value of symmetry. The Egyptians believed their land had been made in the image of the world of the gods and, when someone died, they went to a paradise they would find quite familiar. When an obelisk was made it was always created and raised with an identical twin and these two obelisks were thought to have divine reflections, made at the same time, in the land of the gods. Temple courtyards were purposefully laid out to reflect creation, ma’at, heka (magic), and the afterlife with the same perfect symmetry the gods had initiated at creation. Art reflected the perfection of the gods while, at the same time, serving a practical purpose on a daily basis.