The pyramids are the most recognizable symbol of ancient Egypt. Even though other civilizations, such as the Maya or the Chinese, also employed this form, the pyramid in the modern day is synonymous in most people’s minds with Egypt. The pyramids at Giza remain impressive monuments thousands of years after they were built and the knowledge and skill required to construct them was gathered over the many centuries prior to their construction. Yet the pyramids are not the apex of ancient Egyptian architecture; they are only the earliest and best known expressions of a culture which would go on to create buildings, monuments, and temples just as intriguing.

6,000 Years of History

Ancient Egyptian history begins prior to the Pre-Dynastic Period (c. 6000 – 3150 BCE) and continues through the end of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323 – 30 BCE). Artifacts and evidence of overgrazing of cattle, in the area now known as the Sahara Desert, date human habitation in the area to c. 8000 BCE. The Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 – 2613 BCE) built upon the knowledge of those who had gone before and Pre-Dynastic art and architecture was improved on. The first pyramid in Egypt, Djoser’s Step Pyramid at Saqqara, comes from the end of this Early Dynastic Period and a comparison of this monument and its surrounding complex with the mastaba tombs of earlier centuries show how far the Egyptians had advanced in their understanding of architectural design and construction. Equally impressive, however, is the link between these great monuments and those which came after them.

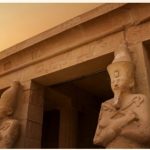

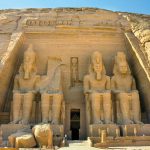

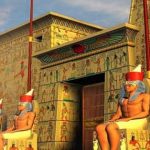

The pyramids at Giza date from the Old Kingdom (c. 2613 – 2181 BCE) and represent the pinnacle of talent and skill acquired at that time. Ancient Egyptian history, however, still had a long and illustrious path before it and as the pyramid form was abandoned the Egyptians focused their attention on temples. Many of these whose ruins are still extant, such as the temple complex of Amun-Ra at Karnak, inspire as much genuine awe as the pyramids of Giza but all of them, however great or modest, show an attention to detail and an awareness of aesthetic beauty and practical functionality which makes them masterpieces of architecture. These structures still resonate in the present day because they were conceived, designed, and raised to tell an eternal story which they still relate to everyone who visits the sites.

EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE & THE CREATION OF THE WORLD

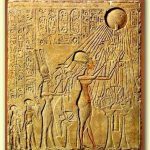

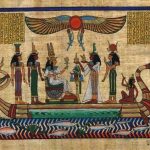

At the beginning of time, according to Egyptian belief, there was nothing but swirling waters of dark chaos. From these primordial waters rose a mound of dry land, known as the ben-ben, around which the waters rolled. Upon the mound lighted the god Atum who looked out over the darkness and felt lonely; so he mated with himself and creation began.

Atum was responsible for the unknowable universe, the sky above, and the earth below. Through his children he was also the creator of human beings (though in some versions the goddess Neith plays a part in this). The world and all that human beings knew came from water, from dampness, moistness, from the kind of environment familiar to the Egyptians from the Nile Delta. Everything had been created by the gods and these gods were ever-present in one’s life through nature.

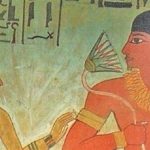

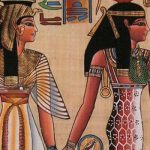

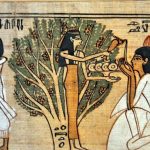

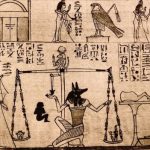

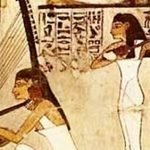

When the Nile River overflowed its banks and deposited the life-giving soil the people depended upon for their crops it was the work of the god Osiris. When the sun set in the evening it was the god Ra in his barge going down into the underworld and the people gladly participated in rituals to make sure he would survive attacks from his nemesis Apophis and rise again the next morning. The goddess Hathor was present in the trees, Bastet kept women’s secrets and protected the home, Thoth gave people the gift of literacy, Isis, although a great and powerful goddess, had also been a single mother who raised her young son Horus in the swamps of the Delta and watched over mothers on earth.

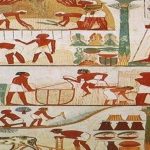

The lives of the gods mirrored those of the people and the Egyptians honored them in their lives and through their works. The gods were thought to have provided the most perfect of worlds for the people of ancient Egypt; so perfect, in fact, that it would last forever. The afterlife was simply a continuation of the life one had been living. It is not surprising, then, that when these people constructed their great monuments they would reflect this belief system. The architecture of ancient Egypt tells this story of the people’s relationship with their land and their gods. The symmetry of the structures, the inscriptions, the interior design, all reflect the concept of harmony (ma’at) which was central to the ancient Egyptian value system.

THE PRE-DYNASTIC & EARLY DYNASTIC PERIODS

In the Pre-Dynastic Period images of the gods and goddesses appear in sculpture and ceramics but the people did not yet have the technical skill to raise massive structures to honor their leaders or deities. Some form of government is evident during this period but it seems to have been regional and tribal, nothing like the central government which would appear in the Old Kingdom.

The homes and tombs of the Pre-Dynastic Period were built of mud brick which was dried in the sun (a practice which would continue throughout Egypt’s history). Homes were thatched structures of reeds which were daubed with mud for walls prior to the discovery of brick making. These early buildings were circular or oval before bricks were used and, after, became square or rectangular. Communities gathered together for protection from the elements, wild animals, and strangers and grew into cities which encircled themselves with walls.

As civilization advanced, so did the architecture with the appearance of windows and doors braced and adorned by wooden frames. Wood was more plentiful in Egypt at this time but still not in the quantity to suggest itself as a building material on any large scale. The mud brick oval home became the rectangular house with a vaulted roof, a garden, and courtyard. Work in mud brick is also evidenced in the construction of tombs which, during the Early Dynastic Period, become more elaborate and intricate in design. These early oblong tombs (mastabas) continued to be built of mud brick but already at this time people were working in stone to create temples to their gods. Stone monuments (stelae) begin to appear in Egypt, along with these temples, by the 2nd Dynasty (c. 2890 – c. 2670 BCE).

Obelisks, large upright stone monuments with four sides and a tapered top, began to appear in the city of Heliopolis at about this time. The obelisk (known to the Egyptians as tekhenu, “obelisk” being the Greek name) is among the most perfect examples of Egyptian architecture reflecting the relationship between the gods and the people as they were always raised in pairs and it was thought that the two created on earth were mirrored by two identical pieces raised in the heavens at the same time. Quarrying, carving, transporting, and raising the obelisks required enormous skill and labor and taught the Egyptians well how to work in stone and move immensely heavy objects over many miles. Mastering stonework set the stage for the next great leap in Egyptian architecture: the pyramid.

Djoser’s mortuary complex at Saqqara was conceived by his vizier and chief architect Imhotep (c. 2667 – c. 2600 BCE) who imagined a great mastaba tomb for his king built of stone. Djoser’s pyramid is not a “true pyramid” but a series of stacked mastabas known as a “step pyramid”. Even so, it was an incredibly impressive feat which had never been achieved before. Historian Desmond Stewart comments on this:

Djoser’s Step Pyramid at Saqqara marks one of those developments that afterward seem inevitable but that would have been impossible without an experimenting genius. That the royal official Imhotep was such a genius we know, not from Greek legend, which identified him with Aesculapius, the god of medicine

but from what archaeologists have discovered from his still impressive pyramid. Investigation has shown that, at every stage, he was prepared to experiment along new lines. His first innovation was to construct a mastaba that was not oblong, but square. His second concerned the material from which it was built (cited in Nardo, 125).

Temple construction, albeit on a modest level, had already acquainted the Egyptians with stonework. Imhotep imagined the same on a grand scale. The early mastabas had been decorated with inscriptions and engravings of reeds, flowers, and other nature imagery; Imhotep wanted to continue that tradition in a more durable material. His great, towering mastaba pyramid would have the same delicate touches and symbolism as the more modest tombs which had preceded it and, better yet, these would all be worked in stone instead of dried mud. Historian Mark Van de Mieroop comments on this:

Imhotep reproduced in stone what had been previously built of other materials. The facade of the enclosure wall had the same niches as the tombs of mud brick, the columns resembled bundles of reed and papyrus, and stone cylinders at the lintels of doorways represented rolled-up reed screens. Much experimentation was involved, which is especially clear in the construction of the pyramid in the center of the complex. It had several plans with mastaba forms before it became the first Step Pyramid in history, piling six mastaba-like levels on top of one another…The weight of the enormous mass was a challenge to the builders, who placed the stones at an inward incline in order to prevent the monument breaking up (56)

When completed, the Step Pyramid rose 204 feet (62 meters) high and was the tallest structure of its time. The surrounding complex included a temple, courtyards, shrines, and living quarters for the priests covering an area of 40 acres (16 hectares) and surrounded by a wall 30 feet (10.5 meters) high. The wall had 13 false doors cut into it with only one true entrance cut in the south-east corner; the entire wall was then ringed by a trench 2,460 feet (750 meters) long and 131 feet (40 meters) wide. The actual tomb of Djoser was located beneath the pyramid at the bottom of a shaft 92 feet (28 meters) long. The tomb chamber itself was encased in granite but, to reach it, one had to traverse a maze of hallways, all brightly painted with reliefs and inlaid with tiles, leading to other rooms or dead ends filled with stone vessels carved with the names of earlier kings. This labyrinth was created, of course, to protect the tomb and grave goods of the king but, unfortunately, it failed to keep out ancient grave robbers and the tomb was looted at some point in antiquity.

Djoser’s Step Pyramid incorporates all of the elements most resonant in Egyptian architecture: symmetry, balance, and grandeur which reflected the core values of the culture. Egyptian civilization was based upon the concept of ma’at (harmony, balance) which was decreed by their gods. The architecture of ancient Egypt, whether on a small or large scale, always represented these ideals. Palaces were even built with two entrances, two throne rooms, two recieving halls in order to maintain symmetry and balance in representing both Upper and Lower Egypt in the design