Ancient Egyptian astronomers may have discovered variable stars, and calculated the period of a well-known one called Algol, thousands of years before Europeans. But they buried those observations in a calendar designed to predict lucky and unlucky days, wrapped in religious narratives, so it’s taken some work for modern scholars to tease out the hidden discovery.

Not all of the stars in the night sky shine steadily. Some, called variable stars, appear to fade and brighten at regular intervals. These stars are actually part of binary systems, and when the dimmer member of the pair passes between us and its brighter sibling, it causes an eclipse, so the bright star seems to fade from the night sky for a few minutes or hours. European astronomers first described a variable star called Mira in 1596, and another called Algol in 1669. John Goodricke calculated the orbital period of Algol’s two stars over a century later, in 1783 — but it turns out the ancient Egyptians had worked that out over a millennium and a half earlier.

It’s worked into the Calendar of Lucky and Unlucky Days, an ancient Egyptian text that recorded which days were likely to be lucky or unlucky, with specific advice for things like travel, feasts, religious offerings, and the likely outcomes of childbirth or illness. The timing of good days and bad followed astronomical events, the timing of the Nile flood, and seasonal shifts in weather.

Certain words — especially the name of the god Horus — pop up at regular intervals that seem to line up with a 2.85 day period. That’s awfully close to Algol’s current 2.867 day period, and in a recent paper in Open Astronomy, astrophysicist Sebastian Porceddu and his colleagues say it makes perfect sense for Algol’s period to have stetched out a bit over the last 3,000 years, because Algol A is slowly losing mass to Algol B, and that transfer bleeds energy and gradually slows the system’s rotation.

But if Algol’s rotation really is behind the pattern of lucky portents written into the Calendar of Lucky and Unlucky Days, it’s a bafflingly obtuse reference, especially for a culture with thousands of years of impressively accurate astronomical observations to its name. Porceddu and others say the Egyptians must have discovered Algol and its variability, because of all the variable stars, it’s the easiest to see and track with the unaided eye.

Egyptian astronomers relied on observations of the night sky for the timing of certain religious rituals; in particular, they looked to “hour-stars,” stars which predictably appeared in certain positions at certain times. “If Algol was not an hour-star, it certainly belonged to some hour-star pattern or related constellation,” Porceddu and his colleagues wrote. And that means the temple astronomers would have noticed when Algol underwent its eclipse. By watching how the timing of the eclipse changed over time, the astronomers could have eventually worked out that it happened regularly, once every 2.85 days.

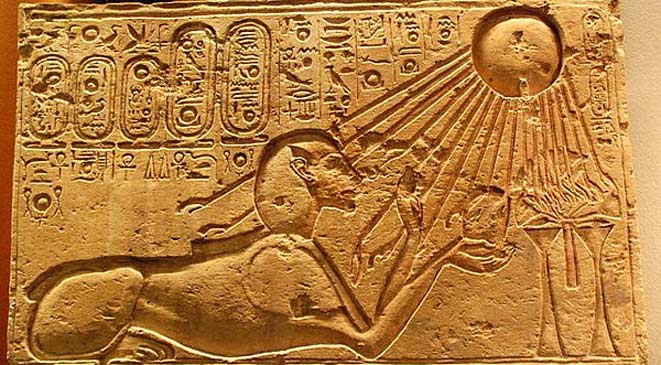

For the Egyptians, whose gods acted out their struggles and journeys against the backdrop of the heavens, a star dimming and brightening as it passed through the night sky would, perhaps, have looked like another piece of the gods’ endless cycles of strife, renewal, and movement. But the ancient astronomers would never have dared describe such a thing directly, because that would threaten the cosmic order that held the kingdom, and the world, together.

“In general, ancient Egyptian scribes seem to have avoided direct references to celestial events, because writing was considered in itself to have a magical power that allows the scribe to communicate with the gods,” wrote Porceddu and his colleagues. But it’s there if you look closely enough at the events from two key Egyptian religious stories, “The Destruction of Mankind” and “The Contendings of Horus and Seth,” which appear throughout the calendar and influence many days’ prognoses. The timing of those events parallels the rotation of Algol and the monthly cycle of the Moon. For example, on the 27th day of the first month of Akhet, the flood season, the calendar records that “the god Horus and his enemy Seth rest from their struggles,” and the scribes recommend that readers avoid killing snakes.

The real surprise is that Algol seems to represent Horus, an Egyptian god with ties to the Sun and embodied by the living pharaoh, and its period is connected to lucky days on the calendar. That sets Egypt apart from most other ancient cultures, which usually saw Algol as harbinger of evil. To the ancient Greeks, the variable star was the “Head of Gorgon.” And in ancient Arabic culture, it was “the head of the ghoul,” and that’s where the modern name Algol comes from. For medieval European astrologers, it represented an ill omen, or the “evil eye.” That makes it a little surprising that these earlier astronomers didn’t actually describe Algol’s variability, since they were obviously paying attention to it — and it seems they noticed something that made them uneasy about the star.

“These names seem to indicate that some exotic or foreboding feature or mutability was known in the folklore of the ancient peoples,” wrote Porceddu and his colleagues. “It is actually surprising that it is so difficult to find any direct reference to Algol’s variability in old astronomical texts.” In 1946, Czech astrnomer Zdeněk Kopal suggested that the missing reference might have been “buried in the ashes of the Library of Alexandria.”

And with such an unsavory reputation in the rest of the ancient world, you might expect Algol to have been linked with the Egyptian god of of disorder and the wild desert, Seth — the ancient enemy of Horus and his father Osiris (also their uncle and brother, respectively; the Egyptians gods were the prototypical dysfunctional family). But the Calendar of Lucky and Unlucky days links Seth’s appearnces more closely to the cycles of the Moon, not Algol. The variable star actually seems to be a lucky omen.

Why? Perhaps for the same reason that Algol so unsettled astronomers from other cultures: its habit of seeming to disappear and reappear. That cycle would have mirrored Horus’s cycle of death and rebirth, making the association pretty obvious. And in many early texts, Horus was associated with a star before his rise to prominence as a solar god.

“Although the Cairo Calendar deals with astronomy only indirectly, it contains evidence that the scribes made recordings of a concrete phenomenon later discovered by modern science: the regular changes of the eclipsing binary Algol,” wrote Porceddu and his colleagues. It would nearly another 1400 years before European astronomers made the same observation.