Life in his palace at Akhetaten seems to have been his primary concern. The city was built on virgin land in the middle of Egypt facing towards the east and precisely positioned to direct the rays of the morning sun toward temples and doorways. The city was:

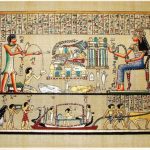

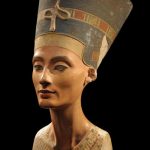

Laid out parallel to the river, its boundaries marked by stelae carved into the cliffs ringing the site. The king himself took responsibility for its cosmologically significant master plan. In the center of his city, the king built a formal reception palace where he could meet officials and foreign dignitaries. The palaces in which he and his family lived were to the north and a road led from the royal dwelling to the reception palace. Each day, Akhenaten and Nefertiti processed in their chariots from one end of the city to the other, mirroring the journey of the sun across the sky. In this, as in many other aspects of their lives that have come to us through art and texts, Akhenaten and Nefertiti were seen, or at least saw themselves, as deities in their own right. It was only through them that the Aten could be worshipped: they were both priests and gods. (Hawass, 39)

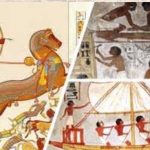

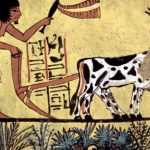

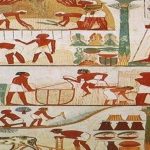

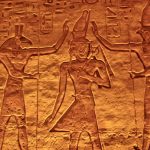

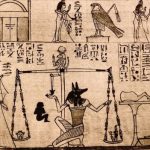

The art Hawass references is another important deviation of the Amarna Period from earlier and later Egyptian eras. Unlike the images from other dynasties of Egyptian history, the art from the Amarna Period depicts the royal family with elongated necks and arms and spindly legs. Scholars have theorized that perhaps the king “suffered from a genetic disorder called Marfan’s syndrome” (Hawass, 36) which would account for these depictions of him and his family as so lean and seemingly oddly-proportioned.

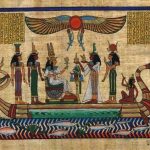

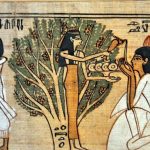

A much more likely reason for this style of art, however, is the king’s religious beliefs. The Aten was seen as the one true god who presided over all and infused all living things. It was envisioned as a sun disk whose rays ended in hands touching and caressing those on earth. Perhaps, then, the elongation of the figures in these images was meant to show human transformation when touched by the power of the Aten.

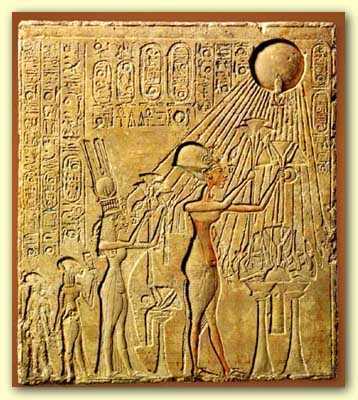

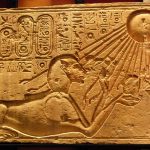

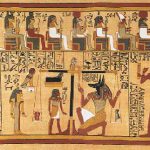

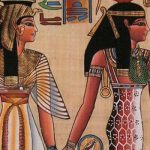

The famous Stele of Akhenaten, depicting the royal family, shows the rays of the Aten touching them all and each of them, even Nefertiti, depicted with the same elongation as the king. To consider these images as realistic depictions of the royal family, afflicted with some disorder, seems to be a mistake in that there would be no reason for Nefertiti to share in the king’s supposed disorder. The depiction, then, could illustrate Akhenaten and Nefertiti as those who had been transformed to god-like status by their devotion to the Aten to such an extent that their faith is seen even in their children.

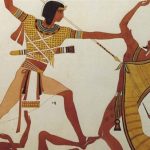

The other aspect of Amarna Period art which differentiates it from earlier and later periods is the intimacy of the images, best exemplified in the Stele of Akhenaten showing the family enjoying each other’s company in a private moment. Images of pharaohs before and after this period depict the ruler as a solitary figure engaged in hunting or battle or standing in the company of a god or his queen in dignity and honor. This can also be explained as stemming from Akhenaten’s religious beliefs in that the Aten, not the pharaoh, was the most important consideration, and under the influence of the Aten’s love and grace, the pharaoh and his family thrives.

Akhenaten’s Monotheism & Legacy

This image of the Aten as an all-powerful, all-loving, deity, supreme creator and sustainer of the universe, is thought to have had a potent influence on the later development of monotheistic religious faith. Whether Akhenaten was motivated by a political agenda to suppress the power of the cult of Amun or if he experienced a true religious revelation, he was the first on record to envision a single, supreme deity who cared for the individual lives and fates of human beings. Sigmund Freud, in his 1939 CE work Moses and Monotheism, argues that Moses was an Egyptian who had been an adherent of the cult of Aten and was driven from Egypt following Akhenaten’s death and the return to the old religious paradigm. Freud quotes from James Henry Breasted, the noted archaeologist, that:

It is important to notice that his name, Moses, was Egyptian. It is simply the Egyptian word ‘mose’ meaning ‘child’, and is an abridgement of a fuller form of such names as ‘Amen-mose’ meaning ‘Amon-a-child’ or ‘Ptah-mose’ meaning ‘Ptah-a-child’…and the name Mose, ‘child’, is not uncommon on the Egyptian monuments. (5)

Freud recognizes that the cult of Aten existed long before Akhenaten raised it to prominence but points out that Akhenaten added a component unknown previously in religious belief: “He added the something new that turned into monotheism, the doctrine of a universal god: the quality of exclusiveness” (24). The Greek philosopher Xenophanes (c. 570 – c. 478 BCE) would later experience a similar vision that the many gods of the Greek city-states were vain imaginings and there was only one true god and, though he shared this vision through his poetry, he never established the belief as a revolutionary new way of understanding oneself and the universe. Whether one regards Akhenaten as a hero or villain in Egypt’s history, his elevation of the Aten to supremacy changed not only that nation’s history, but the course of world civilization.

To those who came after him in Egypt, however, he was the ‘heretic king’ and ‘the enemy’ whose memory needed to be eradicated. His son, Tutankhamun (c. 1336-1327 BCE) was given the name Tutankhaten at birth but changed his name upon ascending the throne to reflect his rejection of Atenism and his return of the country to the ways of Amun and the old gods. Tutankhamun’s successors Ay (1327-1323 BCE) and, especially, Horemheb (c. 1320-1292 BCE) tore down the temples and monuments built by Akhenaten to honor his god and had his name, and the names of his immediate successors, stricken from the record.

In fact, Akhenaten was unknown in Egyptian history until the discovery of Amarna in the 19th century CE. Horemheb’s inscriptions listed himself as the successor to Amenhotep III and made no mention of the rulers of the Amarna Period. Akhenaten’s tomb was uncovered by the great archaeologist Flinders Petrie in 1907 CE and Tutankhamun’s tomb, more famously, by Howard Carter in 1922 CE. Interest in Tutankhamun spread to the family of the ‘golden king’ and so attention was brought to bear again on Akhenaten after almost 4,000 years. His legacy of monotheism, however, if Freud and others are correct, influenced other religious thinkers to emulate his ideal of one true god and reject the polytheism which had characterized human religious belief for millennia.