Art is an essential aspect of any civilization. Once the basic human needs have been taken care of such as food, shelter, some form of community law, and a religious belief, cultures begin producing artwork, and often all of these developments occur more or less simultaneously. This process began in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 – c. 3150 BCE) through images of animals, human beings, and supernatural figures inscribed on rock walls. These early images were crude in comparison to later developments but still express an important value of Egyptian cultural consciousness: balance.

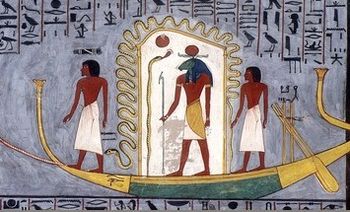

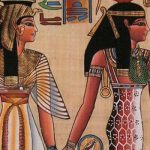

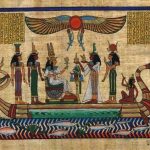

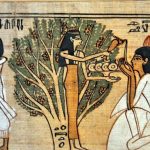

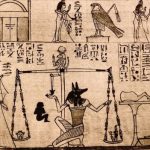

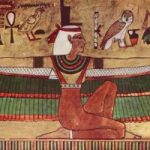

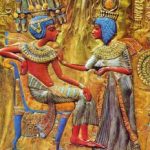

Egyptian society was based on the concept of harmony known as ma’at which had come into being at the dawn of creation and sustained the universe. All Egyptian art is based on perfect balance because it reflects the ideal world of the gods. The same way these gods provided all good gifts for humanity, so the artwork was imagined and created to provide a use. Egyptian art was always first and foremost functional. No matter how beautifully a statue may have been crafted, its purpose was to serve as a home for a spirit or a god. An amulet would have been designed to be attractive but aesthetic beauty was not the driving force in its creation, protection was. Tomb paintings, temple tableaus, home and palacegardens all were created so that their form suited an important function and, in many cases, this function was a reminder of the eternal nature of life and the value of personal and communal stability.

Early Dynastic Period Art

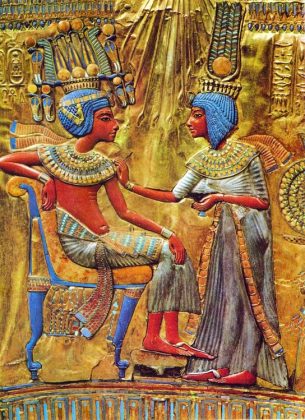

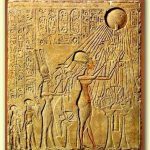

The value of balance, expressed as symmetry, infused Egyptian art from the earliest times. The rock art from the Predynastic Period establishes this value which is fully developed and realized in the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (c. 3150 – c. 2613 BCE). Art from this period reaches its height in the work known as The Narmer Palette (c. 3200-3000 BCE) which was created to celebrate the unity of Upper and Lower Egypt under King Narmer (c. 3150 BCE). Through a series of engravings on a siltstone slab, shaped as a chevron shield, the story is told of the great king’s victory over his enemies and how the gods encouraged and approved his actions. Although some of the images of the palette are difficult to interpret, the story of unification and the celebration of the king is quite clear

On the front, Narmer is associated with the divine strength of the bull (possibly the ApisBull) and is seen wearing the crown of Upper and Lower Egypt in a triumphal procession. Below him, two men wrestle with entwined beasts which are often interpreted as representing Upper and Lower Egypt (though this view is contested and there seems no justification for it). The reverse side shows the king’s victory over his enemies while the gods look on approvingly. All these scenes are carved in low-raised relief with incredible skill.

This technique would be used quite effectively toward the end of the Early Dynastic Period by the architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE) in designing the pyramid complex of King Djoser (c. 2670 BCE). Images of lotus flowers, papyrus plants, and the djed symbol are intricately worked into the architecture of the buildings in both high and low relief. By this time the sculptors had also mastered the art of working in stone to created three-dimensional life-sized statues. The statue of Djoser is among the greatest works of art from this period.

Old Kingdom Art

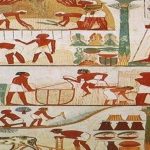

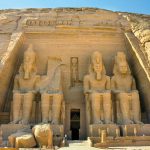

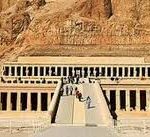

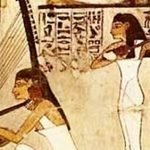

This skill would develop during the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) when a strong central government and economic prosperity combined to allow for monumental works like the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Sphinx, and elaborate tomb and temple paintings. The obelisk, first developed in the Early Dynastic Period, was refined and more widely used during the Old Kingdom. Tomb paintings became increasingly sophisticated but statuary remained static for the most part. A comparison between the statue of Djoser from Saqqara and a small ivory statue of King Khufu (2589-2566 BCE) found at Giza display the same form and technique. Both of these works, even so, are exceptional pieces in execution and detail

Art during the Old Kingdom was state mandated which means the king or a high-ranking nobility commissioned a piece and also dictated its style. This is why there is such uniformity in Old Kingdom artwork: different artists may have had their own vision but they had to create in accordance with their client’s wishes. This paradigm changed when the Old Kingdom collapsed and initiated the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE).