1. Muslim Heritage in mechanics and technology: milestones in century long research

I am so glad and honored to be among you in this meeting and to address your venerable assembly as a new member of the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation in Manchester, an institution with which I share the approach and the method in disseminating knowledge about Muslim scientific and technological achievements.

The history of Islamic science has undergone great progress in the last three decades. The field has been almost completely rewritten. A great deal of work has been done in the study of Islamic technology and engineering. In this field, two main series of contributions must be mentioned: the work of the German school – mainly by Eilhard Wiedemann and his collaborators in the first quarter of the 20th century, and the research conducted by Donald Hill, Ahmad Yûsuf al-Hassan and their collaborators in the last quarter of the 20thcentury.

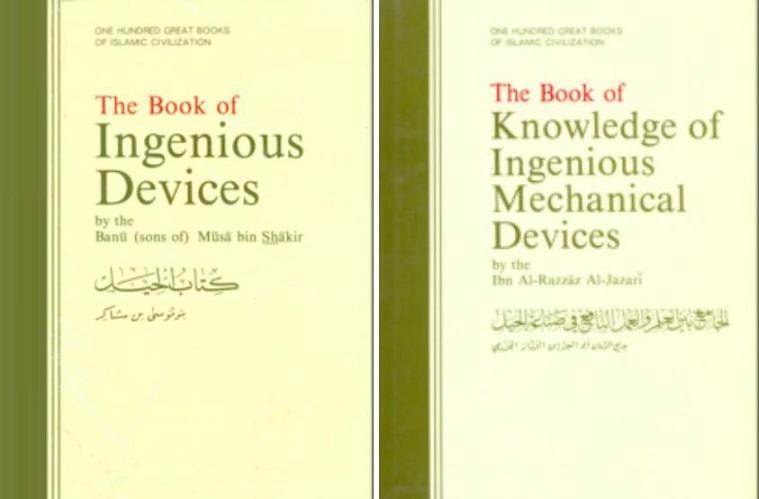

|

|

Figure 2b: Front cover of Islamic Technology: An Illustrated History by A.Y. Al-Hassan and D.R. Hill (Cambridge University Press, 1986). |

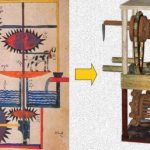

These two phases of scholarship established an inventory of the available knowledge and highlighted important aspects of the Muslim contribution to practical mechanics and engineering. Hence, significative texts were edited and translated, mainly the treatises of machines by Banū Mūsā, al-Jazarī and Taqī al-Dīn Ibn Ma’rūf. The book Islamic Technology by Hill and al-Hassan, published in 1986, produced a comprehensive survey of the field that showed the richness of Islamic technology and its various social and economic dimensions.

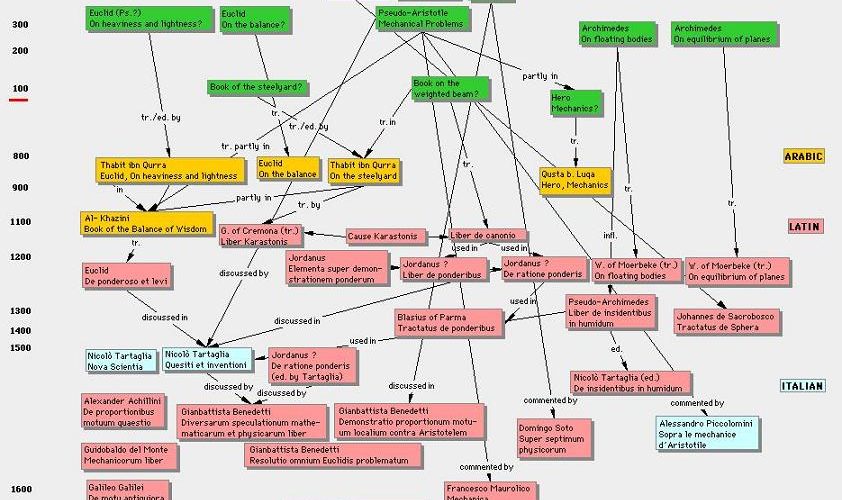

In theoretical mechanics, a main contribution is represented by the reconstruction of the corpus of the Arabic ‘ilm al-athqāl or the science of weights, a field touched upon previously by scholars in a very limited way but of which the scope remained uncovered. In the late 1990s, I had the privilege and honour to design an overall project of research to reconstruct the textual corpus of the Arabic science of weights. This project was supported by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin with which I collaborated for several years. The first outcome of this research project stressed on one hand the Arabic transformation of Greek mechanics into an independent theoretical branch, and on the other hand made clear that the history of medieval mechanics is an intercultural history in which many common features shape both the Arabic ‘ilm al-athqāl and the Latin scientia de ponderibus. As my work has proven, the latter rose in Europe from the 13thcentury onwards in the works attributed to Jordanus and was at least partially a direct outcome of the translation of Arabic mechanical materials [for references, see the extensive bibliography appended below].

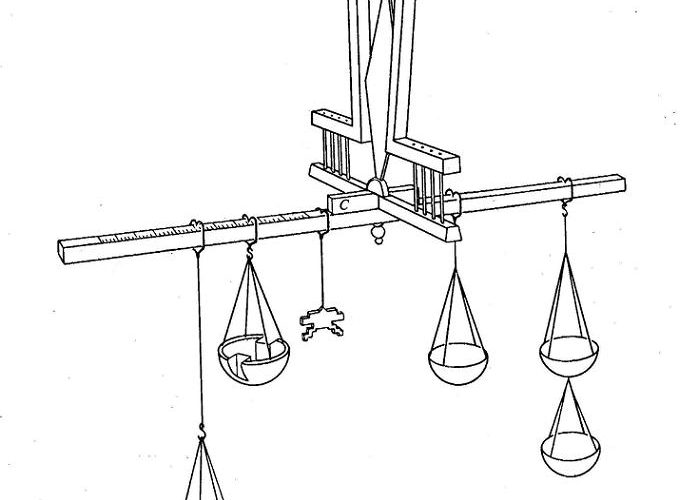

In this respect, let me point out that among representative instruments relevant to the research on the science of weights are two Islamic steelyard balances kept in the Science Museum in London. The largest one has a wrought-iron beam of 2.37m long that can weigh until 1820 pounds. The smaller one is a medium balance of about 1.30m.

|

|

Figure 5: Intercultural history of theoretical mechanics: Greek-Arabic-Latin. |

The outstanding and unprecedented work done by Professor Salim al-Hassani and the FSTC on Al-Jazarī’s machines yielded a new approach to the historical objects by reconstructing animated models of them so that we see the machines in action and understand their principles and functions. This approach was applied to the famous pump for raising water of Al-Jazarī and explained the transmission of force on the basis of the conversion of circular motion in rectilinear displacement, a discovery that has been credited for decades to Leonardo da Vinci, but which was performed by al-Jazarī three centuries earlier. This approach may be applied to a large variety of machines and will show the same efficiency. Indeed, when we see the machine working on the animation, it is hard to say, as some historians did, that the machines described in Arabic mechanical treatises were just toys or imaginary devices.