In Ancient Egypt, social dignity was not based on gender, but rather on social status (Jeyawordena, 1986; Robins, 1993; Piccione, 2003; Nardo, 2004; Hunt, 2009; Cooney, 2014). This means that women held many important and influential positions in Ancient Egypt and typically enjoyed many of the legal and economic rights given to the men within their respective social class.

Social Life

Unlike other ancient societies, women in Ancient Egypt had a high degree of equal opportunity and freedom (Nardo, 2004). Ancient Egyptians (women and men) were firmly equal. Interestingly, ancient sources indicate that women were qualified to sue and obtain contracts incorporating any lawful settlements, such as marriage, separation, property, and jobs (Hunt, 2009). Some of these rights are not given to women in modern-day Egypt. Furthermore, the historian Herodotus witnessed an exceptional display of humanity and equality in Ancient Egypt that was not present in other ancient societies (Tyldesley, 1995).

Art and Music

Gifted women actively participated in the weaving, grieving, and music organizations in Ancient Egypt. Moreover, being a professional in entertainment was another job that was occupied by women in Ancient Egypt (Hunt, 2009).Yet; there is no proof that they ever regulated male laborers, except the most senior imperial women. Hekenu and Iti were two eminent musicians of the Old Kingdom (Figure1A). These women were popular to the point that they even had their performances painted on other people’s tombs, which was a special privilege since it was common to only incorporate individuals from the perished family in the scenes (Hunt, 2009).

Other recorded occupations of Ancient Egyptian women were hair specialists, supervisors of the wig workshop, treasurers, writers, songstress, weavers, dancers, musicians, grievers, priestess’, and even directors of the imperial kingdom. One such recorded occupation was that of “Judge and Vizier to Pharaoh.” This position was held by a woman called “Nebet of the Old kingdom.” The “vizier” was the most capable individual after the lord Pharaoh, going about as his “correct hand man.” However, it is thought that “Nebet’s husband directed in the post whilst she held the title” (Figure1B).

Marriage

Unlike other societies, Ancient Egyptian women were not subservient to men, were able to choose suitable men for a wedding, and were also able to separate from their husbands (Jacobs, 1996; Hunt, 2009).

Reported contracts affirmed fairness between men and women, expressing women’s rights and ensured equality in employment. For example, an annuity contract found in an archive of Ptolemaic “Family from Suit Nefertiti” illustrates how a divorced Egyptian woman got what was relating to her legacy which she used to share amid marriage. Ancient Egyptian women also had the capacity of unreservedly arranging and fulfilling the terms of her possessions in her contract before going into any marriage plan (Tyldesley, 1994).

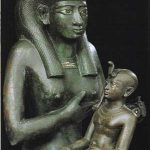

Several Papyri indicated the capacity of Ancient Egyptian women to gain wealth independently from their husbands. On the other hand, a husband could lawfully treat his wife as his legal “child,” if he did not want to give any of his riches to his relatives. This way, the wife could acquire the greater part of his riches if they had no children together, or 66% if they had children. The Ancient Egyptian culture believed that a content and delighted home life ought to be the standard. They believed that it could be only accomplished by a husband and his wife, indulgent and administering to one another according to the guideline of Maat (Figure1C) (Tyldesley, 2006).

Financial Rights

Ancient Egyptian women were able to settle on monetary choices independently, for example when possessing a property. When entering a marriage, women could claim joint property with their husbands. This implies that if the husband was to discard any joint property, then he was lawfully bound to reward his wife with a property of the same worth (Dayan-Herzbrun, 2005).

Inscriptions and sketches portraying women and men going to feasts; hunting and fishing together is an indicator of the equal union of men and women in social life. In addition, tombs enriched with artwork of deceased women dressed extravagantly in the most recent design using aroma, beautifiers, and toiletries. The gifts for life following death were expressions of men’s fondness for their wives.

Religion

The French Egyptologist, Nobelcouer, indicated the representation of equity between men and women during the Ancient Egyptian times in resembling Gods. For instance, temples, engravings, divider compositions, and also statues displaying powerful and intense female divinities indicates that both genders were regarded as equals and that women were not subservient to men. Prime examples are some prominent female goddesses, including the following: Maat (Figure1C) who had all powers and energy; Isis, the Ancient Egyptian Goddess who is similar to Hathor (Graves-Brown, 2010), the goddess of claiming reverence and recuperating. Most importantly, one papyrus exhibited Isis (Manning, 2012) as in control of certain affairs as much as men. These female divinities were as essential and crucial as male divine creatures for Egyptians during that time. Seemingly, the goddess Bastet, a champion around the vast majority of Egyptian gods, figured out how to enhance women’s well-being, security, and labor. People in Ancient Egypt put Bastet in the same level of respect and admiration as Ancient Egyptian women.

Medicine

Throughout the ancient history of Egypt, there were more than 100 noteworthy female specialists recorded in every domain of medicine. These women were very educated and highly regarded in their specialization, with pictures showing up on tomb dividers, and hieroglyphics scratched. Among the most imperative female doctors of this time was Peseshet (Figure 1D). As seen in engravings found in a tomb of an Old Kingdom, nearly at 3100 B.C.–2100 B.C., she was known as an “administrator of specialists.” Peseshet was a doctor in her specialization, an administrator, and the executive to a group of female doctors. Another significant female doctor from Ancient Egypt was Merit Ptah (Figure1E); she was the first-ever named doctor and the first woman in the historical backdrop of the pharmaceutical field. In this context, she rehearsed pharmaceutical science almost 7,000 years ago, and was deified by her child on her tomb as “The boss doctor.” Another remarkable Ancient Egyptian woman made her print on the field of obstetrics and gynecology, subsequently, in the second century A.D., a doctor named Cleopatra (not the long-dead previous Queen). Cleopatra wrote widely about pregnancy, labor, and women’s well-being, her writings were consulted and examined for more than 1,000 years afterward (Rossiter, 1982).

Furthermore, records exist about Egyptian female doctors, such as Merit Ptah, 2700 B.C and Zipporah, 1500 B.C. Therefore, Egyptian women of ancient times were privileged, as they were able to seek their dreams, strengthen their family life, study, and achieve progress in their work. This led to Egyptian women being among the most regarded doctors of their time.