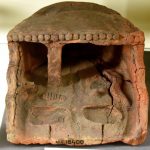

In ancient Egypt, if a woman were having difficulty conceiving a child, she might spend an evening in a Bes Chamber (also known as an incubation chamber) located within a temple. Bes was the god of childbirth, sexuality, fertility, among other his other responsibilities, and it was thought an evening in the god’s presence would encourage conception. Womenwould carry Bes amulets, wear Bes tattoos, in an effort to encourage fertility.

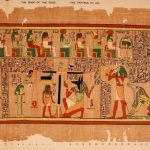

Once a child was born, Bes images and amulets were used in protection as he or she grew and, later, the child would become an adult who adopted these same rituals and beliefs in daily life. At death, the person was thought to move on to another plane of existence, the land of the gods, and the rituals surrounding burial were based on the same understanding one had known all of one’s life: that supernatural powers were as real as any other aspect of existence and the universe was infused by magic.

Magic in ancient Egypt was not a parlor trick or illusion; it was the harnessing of the powers of natural laws, conceived of as supernatural entities, in order to achieve a certain goal. To the Egyptians, a world without magic was inconceivable. It was through magic that the world had been created, magic sustained the world daily, magic healed when one was sick, gave when one had nothing, and assured one of eternal life after death. The Egyptologist James Henry Breasted has famously remarked how magic infused every aspect of ancient Egyptian life and was “as much a matter of course as sleep or the preparation of food” (200). Magic was present in one’s conception, birth, life, death, and afterlife and was represented by a god who was older than creation: Heka.

Heka

Heka was the god of magic and the practice of the art itself. A magician-priest or priest-physician would invoke Heka in the practice of heka. The god was known as early as the Pre-Dynastic period (c. 6000-c. 3150 BCE), developed during the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) and appears in The PyramidTexts of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) and the Coffin Texts of the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE). Heka never had a temple, cult following, or formal worship for the simple reason that he was so all-pervasive he permeated every area of Egyptian life.

Like the goddess Ma’at, who also never had a formal cult or temple, Heka was considered the underlying force of the visible and invisible world. Ma’at represented the central Egyptian value of balance and harmony while Heka was the power which made balance, harmony, and every other concept or aspect of life possible. In the Coffin Texts, Heka claims this primordial power stating, “To me belonged the universe before you gods came into being. You have come afterwards because I am Heka” (Spell 261). After creation, Heka sustained the world as the power which gave the gods their abilities. Even the gods feared him and, in the words of Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson, “he was viewed as a god of inestimable power” (110). This power was evident in one’s daily life: the world operated as it did because of the gods and the gods were able to perform their duties because of Heka.