Instructions on how one would animate a shabti in the next life, as well as how to navigate the realm which waited after death, was provided through the texts inscribed on tomb walls and, later, written on papyrus scrolls. These are the works known today as the Pyramid Texts (c. 2400-2300 BCE), the Coffin Texts (c. 2134-2040 BCE), and The Egyptian Book of the Dead (c. 1550-1070 BCE). The Pyramid Texts are the oldest religious texts and were written on the walls of the tomb to provide the deceased with assurance and direction.

When a person’s body finally failed them, the soul would at first feel trapped and confused. The rituals involved in mummification prepared the soul for the transition from life to death, but the soul could not depart until a proper funeral ceremony was observed. When the soul woke in the tomb and rose from its body, it would have no idea where it was or what had happened. In order to reassure and guide the deceased, the Pyramid Texts and, later, Coffin Texts were inscribed and painted on the inside of tombs so that when the soul awoke in the dead body it would know where it was and where it now had to go.

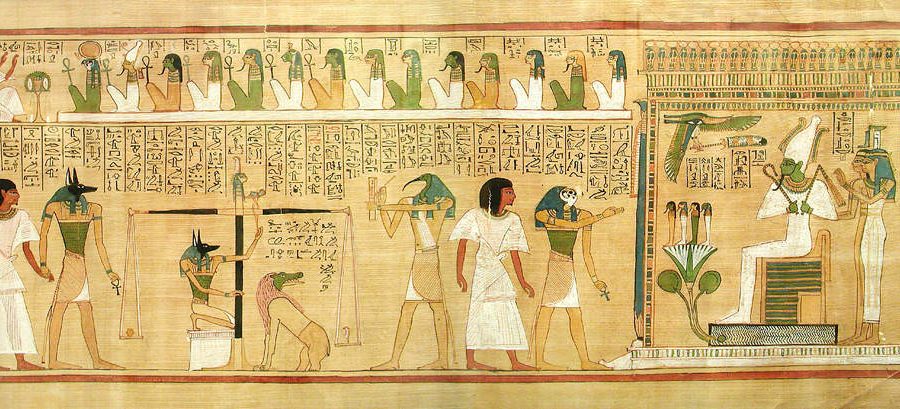

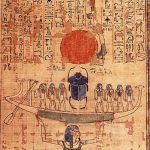

These texts eventually turned into The Egyptian Book of the Dead (whose actual title is The Book of Coming Forth by Day), which is a series of spells the dead person would need in order to navigate through the afterlife. Spell 6 from the Book of the Dead is a rewording of Spell 472 of the Coffin Texts, instructing the soul in how to animate the shabti. Once the person died and then the soul awoke in the tomb, that soul was led – usually by the god Anubis but sometimes by others – to the Hall of Truth (also known as The Hall of Two Truths) where it was judged by the great god Osiris. The soul would then speak the Negative Confession (a list of ‘sins’ they could honestly say they had not committed such as ‘I have not lied, I have not stolen, I have not purposefully made another cry’), and then the heart of the soul would be weighed on a scale against the white feather of ma’at, the principle of harmony and balance.

If the heart was found to be lighter than the feather, then the soul was considered justified; if the heart was heavier than the feather, it was dropped onto the floor where it was eaten up by the monster Amut, and the soul would then cease to exist. There was no ‘hell’ for eternal punishment of the soul in ancient Egypt; their greatest fear was non-existence, and that was the fate of someone who had done evil or had purposefully failed to do good.

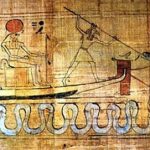

If the soul was justified by Osiris then it went on its way. In some eras of Egypt, it was believed the soul then encountered various traps and difficulties which they would need the spells from The Book of the Dead to get through. In most eras, though, the soul left the Hall of Truth and traveled to the shores of Lily Lake (also known as The Lake of Flowers) where they would encounter the perpetually unpleasant ferryman known as Hraf-hef (“He Who Looks Behind Himself”) who would row the soul across the lake to the paradise of the Field of Reeds. Hraf-hef was the ‘final test’ because the soul had to find some way to be polite, forgiving, and pleasant to this very unpleasant person in order to cross.

Once across the lake, the soul would find itself in a paradise which was the mirror image of life on earth, except lacking any disappointment, sickness, loss, or – of course – death. In The Field of Reeds the soul would find the spirits of those they had loved and had died before them, their favorite pet, their favorite house, tree, stream they used to walk beside – everything one thought one had lost was returned, and, further, one lived on eternally in the direct presence of the gods.

Pets & the Afterlife

Reuniting with loved ones and living eternally with the gods was the hope of the afterlife but equally so was being met by one’s favorite pets in paradise. Pets were sometimes buried in their own tombs but, usually, with their master or mistress. If one had enough money, one could have one’s pet cat, dog, gazelle, bird, fish, or baboon mummified and buried alongside one’s corpse. The two best examples of this are High Priestess Maatkare Mutemhat (c. 1077-943 BCE) who was buried with her mummified pet monkey and the Queen Isiemkheb (c. 1069-943 BCE) who was buried with her pet gazelle.

Mummification was expensive, however, and especially the kind practiced on these two animals. They received top treatment in their mummification and this, of course, represented the wealth of their owners. There were three levels of mummification available: top-of-the-line where one was treated as a king (and received a burial in keeping with the glory of the god Osiris); middle-grade where one was treated well but not that well; and the cheapest where one received minimal service in mummification and burial. Still, everyone – rich or poor – provided their dead with some kind of preparation of the corpse and grave goods for the afterlife.

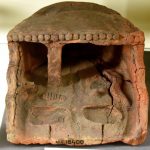

A mummified cat from Egypt, late Ptolemaic Period. (Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, San Jose, California).