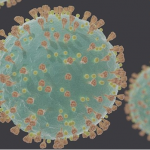

Coronavirus hospitalizations are expected to peak in Chicago, Illinois, at some point in the next two weeks. In an attempt to prevent the kind of medical supply shortages seen in New York City, average Chicagoans are racing to fulfill the need.

On 16 March, in accordance with Illinois Governor JB Pritzker’s order that all bars and restaurants stop serving customers in-house, Dimo’s Pizza in Chicago closed its dining room doors. MHub has switched gears to make masks and shields for doctors and other frontline workers

“We can no longer serve by the slice,” says owner Dimitri Syrkin-Nikolau. “There goes 70% of our revenue.”

Still, Syrkin-Nikolau agreed that the measures were necessary. He’d been following news about the coronavirus outbreak for weeks and on the same weekend that Illinois shuttered its restaurants, New York City experienced the beginning of a terrifying surge in cases. From 15 March to 16 March, the numbers of cases more than doubled overnight. Nurses and doctors reported shortages of essential pieces of personal protective equipment (PPE) like N95 face masks, gowns and gloves. Some were having to wash and re-use masks. New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio warned the city could run out of medical supplies in a matter of days.

Watching from 800 miles away, in a major metropolitan city that had not yet — but certainly would — feel the full force of the pandemic, Syrkin-Nikolau wanted to help prevent a similar shortage of supplies in Chicago.

“It seems unlikely that a pizza shop is going to be able to produce PPE, but the more I talked to people…” he recalls. “It seems far-fetched but it’s not.”

After consulting with a couple of his engineer friends and procuring large sheets of acrylic, Syrkin-Nikolau and his staff have started making face shields for healthcare workers. The industrial pizza oven heats the acrylic up until it’s soft enough to bend into the right shape, and then it is attached to a foam strip and straps.

“It really is a very quick process,” he says. “Whether it’s slinging slices or slinging acrylic, it’s similar principles.”

All over the city, Chicagoans are racing to take advantage of the lag time between the surge in New York City and the expected surge in Chicago, which at this point may have already begun. On Thursday, Governor Pritzker announced the largest single-day increase in COVID-19 deaths so far in the state: 82. As of 9 April, there have been 6,619 cases in the city of Chicago and 196 deaths.

While none of the largest Chicago-area hospitals have reported a shortage of supplies, Illinois officials have described the marketplace for those supplies as “the wild west”. In one instance, a state employee had to race to a bank with a check for $3.4m (£2.7m) in order to purchase 1.5m N95 masks from a supplier in China before other bidders could snap them up. Smaller hospitals that serve low-income Chicagoans, like Loretto Hospital on the West Side, have expressed concern that their stock of masks and gowns is low ahead of the surge.

Those concerns have inspired Chicagoans like Jacqueline Morano, a member of the Masks for Chicago campaign, to do everything possible to collect, make or buy PPE.

“There’s the potential for things to get scary. We are a metropolis,” she says. “The texts I get from my friends in New York City hospitals are things you’d never want to read in your lifetime.”

The campaign Morano has been raising money for, Masks for Chicago, is attempting to source and purchase 1 million N95 masks using one of its founders’ manufacturing contacts in Shenzhen, China. They estimate that should be enough to cover five Chicago hospitals for two weeks. They’ve already received 44,150 masks and have placed orders for over 75,000 more, jostling alongside other cities and even countries as they try to secure orders.

These efforts are happening on both large and small scales throughout the city. Michael Clifford, a former patent lawyer who recently went full-time with his DIY home improvement YouTube channel, began using his 3-D printer to produce plastic browbands for face shields. He got the plans from others in the global maker community who are sharing them for free. When the Masks for Chicago campaign received 500 N95 masks with broken straps, Clifford printed a batch of S-hooks to easily re-attach them. He just purchased a second 3-D printer to try to increase production.

“Beyond Chicago, there’s people doing this all over the world right now,” he says.

In some cases, hospitals are reaching out directly. Haven Allen is the CEO and cofounder of MHub, a nonprofit with 350 small- and medium-sized member companies that center around manufacturing. After shutting down its 63,000-square-foot facility on 13 March, Allen says it was obvious to him that MHub’s onsite equipment, materials and idle engineers could still be used to help Chicago-area hospitals with their supply shortage. Their first project — build a cheap, easy-to-manufacture ventilator from materials one could buy off the shelf.

“We wanted to drive down the price point to about $350 a unit,” he says.

Then Northwestern Memorial Hospital called. They were concerned about a shortage of face shields. Allen and a few volunteer engineers quickly switched gears.

“Within just a few hours, they created a few prototypes with the materials they had on site,” writes Megan McCann, a spokeswoman for Northwestern, in an email to the BBC. “The first batch of face shields was delivered to Northwestern Memorial Hospital the week of March 30; these will go directly to the doctors, nurses and staff caring for patients with Covid-19.”

Allen says prototypes for the ventilators will be ready this week, and that he wants to make the plans free and available to anyone who wants to replicate them.

Using PPE from volunteers, DIY makers and from unvetted suppliers in China, as opposed to through approved vendors, can be tricky for hospitals. Certain products have to be approved by the Centers for Disease Control or the Food and Drug Administration before a hospital can accept them. But with products as simple as face shields — and with fear of infection so high — some healthcare workers seem to be willing to use whatever is provided to them in lieu of nothing.

“Can I make something that’s 95% as good as what 3M would make? It’s not perfect, but it’s still 95% better than nothing,” says Clifford. “We can’t argue about the little things. We have to make sure we have the best protection we can because of the shortage.”

Tricia Rae Pendergrast is a first-year medical student and a leader of a group of 400 Chicago-area medical students who are spending their time calling local businesses and soliciting donations of N95 masks, protective suits and other PPE. She says they have the most success with area labs and construction companies, but that they can’t donate to hospitals. Instead, they put them directly into the hands of healthcare workers who ask for them.

“They’re making the decision to use them. They understand they’re not the normal protective equipment,” she says. “In times of crisis, in scarce limited resources, there’s ethical and legal precedent to do the most good for the most people and that’s what we’re doing here.”

At Dimo’s Pizza, Syrkin-Nikolau says they’ve been able to fulfill a few orders for smaller organizations, like a home for elderly homeless people and a small pediatrics practice. He estimates they can make 3,000 shields a week. And while he says he can’t afford to give the shields away, by selling them for $3 a piece he can keep his workers employed and make supplies available during the Chicago coronavirus case surge.

“Everywhere I look, across every segment, everyone is pitching in to do whatever they can any way they can as soon as they possibly can,” he says. “I think that’s the one thing I’m holding on to.”