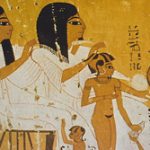

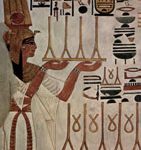

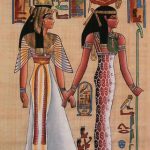

These tattoos are thought to have been worn by a priestess to honor Hathor who, among her many duties, was also goddess of fertility. They were worn by other women as symbolic protection of a child in the womb and during child birth (although these are not mutually exclusive since priestesses could marry and have children). It has been noted that, as a woman’s pregnancy developed and the belly swelled, the tattoos would have formed an intricate net design from one’s lower back to just below one’s navel, thus creating a distinctive protective barrier between the world and the unborn child. The protective aspect of the tattoo is further suggested by the figure of the protector-god Bes which women had tattooed on their inner thigh. Joann Fletcher notes:

This is supported by the pattern of distribution, largely around the abdomen, on top of the thighs and the breasts, and would also explain the specific types of designs, in particular the net-like distribution of dots applied over the abdomen. During pregnancy, this specific pattern would expand in a protective fashion in the same way bead nets were placed over wrapped mummies to protect them and “keep everything in.” The placing of small figures of the household deity Bes at the tops of their thighs would again suggest the use of tattoos as a means of safeguarding the actual birth, since Bes was the protector of women in labor, and his position at the tops of the thighs a suitable location. This would ultimately explain tattoos as a purely female custom. (1)

No written work on the subject of tattoos survives from ancient Egypt and so interpretation is always speculative but it seems likely these tattoos were not simply adornments to make a woman more attractive to a man but served a higher purpose and, further, this purpose differed in different eras. Graves-Brown writes:

Much confusion also arises from the conflation of New Kingdom depictions of Bes on dancers’ legs, with Middle Kingdom marks on the bodies of elite women and `fertility dolls’. All the evidence suggests that the only Egyptians in Dynastic Egypt to have tattoos were women and that these women would be elite court ladies and priestesses of Hathor perhaps decorated to ensure fertility, but not for the simple amusement of men. The origins and precise meaning of the tattoos, however, remain unclear .

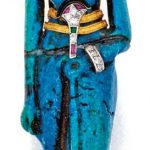

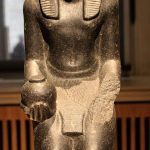

Bes, Museo Barracco

Bes was primarily a protector god of pregnant women and children but was also associated with sexuality, fertility, humor, and joy in life. His image on a woman’s thigh, therefore, could have many meanings within that context and should not be interpreted narrowly as only pertaining to sexual attraction. Tyldesley writes:

Some New Kingdom entertainers and servant girls displayed a small picture of the dwarf god Bes high on each thigh as a good luck symbol and a less than subtle means of drawing attention to their hidden charms. It has been suggested that this particular tattoo may have been the trade mark of a prostitute, but it seems equally likely to have been worn as an amuletic guard against the dangers of childbirth, or even as a protection against sexually transmitted diseases (160).

Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch also makes a point of the many ways in which Bes tattoos could be interpreted, writing, “Bes amulets and figurines were popular for over 2,000 years. Some women even decorated their bodies with Bes tattoos to improve their sex life or fertility” (118). It does seem clear that prostitutes wore tattoos based upon engravings and images such as those on the Turin Erotic Papyrus. The Turin Erotic Papyrus is a badly damaged document dating from the latter part of the New Kingdom (the Ramesside Period c. 1186-1077 BCE). Interpretations of the images range from claims it depicts a brothel, is a satire on sexual mores, or shows the sexual practices of the gods. The brothel interpretation goes directly to the Bes tattoo as a mark of prostitutes in that one of the women in the images is shown with the tattoo on her upper thigh.

It should be noted, however, that this interpretation is by no means accepted by every scholar who has worked with the papyrus nor should one assume that, because a prostitute wears a certain tattoo, piece of jewelry, or article of clothing, that those images, objects, and articles are synonymous with prostitution. Tattoos seem to have been worn by a number of different kinds of women for different reasons.

Tattoo Artists & Tools

The British archaeologist W. M. Flinders Petrie (1853-1942 CE) discovered tattooing tools at Abydos and the town of Gurob dating to c. 3000 BCE and c. 1450 BCE respectively. The Abydos kit consisted of sharp metal points with a wooden handle while the Gurob kit’s needles were bronze. Based upon the tattoos on the mummies, the tattoo artists used a dark pigment of dye, most likely black, blue, or green, with little variation.

These colors symbolized life, birth, resurrection, the heavens, and fertility. Although the color black in the modern day is usually associated with death and evil, in ancient Egypt it symbolized life and resurrection. Green was commonly used as a symbol of life and blue, among its many meanings, symbolized fertility and birth. The tattoo artists were most likely older women with experience understanding both the symbols and the significance of the colors. Female seers were commonplace in ancient Egypt, as Egyptologist Rosalie David explains:

In the Deir el-Medina texts, there are references to ‘wise-women’ and the role they played in predicting future events and their causation. It has been suggested that such seers may have been a regular aspect of practical religion in the New Kingdom and possibly even in earlier times. (281)

One of the principal purposes assumed for the Egyptian tattoos is practical magic and it is probable that women were tattooed by the female seers for this reason. Images drawn for protection, whether on structures, objects, or people, was commonplace in Egypt. Mothers would frequently draw a picture of Bes on their children’s palm and then wrap the hand in a blessed cloth to encourage pleasant dreams. Magical amulets, of course, were popular throughout Egypt in all periods. Magic was synonymous with medicine in Egypt and recognized as an important aspect of life. Magical images, then, tattooed on one’s skin would hardly have been out of place no matter one’s social status.