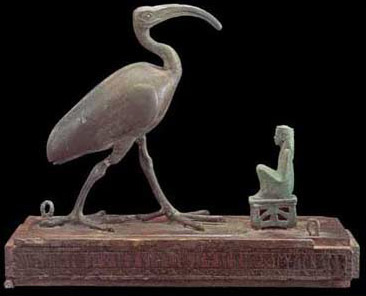

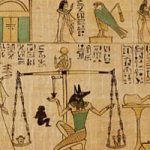

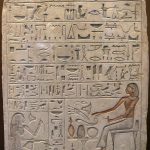

There was no word known to us from ancient Egypt with the specific meaning of “science”. The word Rh, “to know” probably comes closest, but it had a wide range of meanings. This is perhaps understandable, as our current definition of science is rather broad. We define it as the observation, identification, description, experimental investigation and theoretical explanation of phenomena. Otherwise, it is knowledge, especially gained through experience. Knowledge itself was the domain of the god Thoth in ancient Egypt, who was the patron deity of scribes. It was the scribes who were almost exclusively responsible for ancient Egyptian science, usually in either a priestly role, or that of administrators.

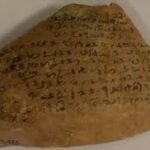

Our understanding of ancient Egyptian science originates from various sources, including artifacts, tomb paintings, inscriptions and papyri. Nevertheless, our knowledge of ancient Egyptian science is incomplete, though expanding. At the same time, there is also no reason to believe that the ancient Egyptians had any special hidden knowledge, in general, that has since been los

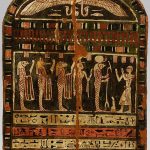

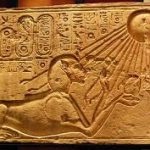

Though the ancient Egyptians probably did not classify science in the same manner we do today, various evidence points to certain disciplines. These included anatomy (for art), astronomy and astrology, which were inseparably linked in ancient Egypt, biology and veterinary medicine, chemistry, geography, geology, history, law, linguistics, mathematics, including geometry, medicine, mineralogy, pedagogy (education), philosophy, physics, particularly related to mechanics, sociology and theology. Often, magic was perhaps not so much thought of as an individual science, but an aspect of many of the disciplines.And an essential feature of ancient Egyptian science was its close ties with theology and with the prevailing notion of a world created in its entirety by gods, perfectly ordered and unchanging.

Yet, there was a profound difference between modern science and ancient Egyptian science. While the modern scientist tries investigating phenomena by experiment, analysis and a continual process of advancing hypotheses which either prove inadequate and are replaced by others, or else lead to a general theory or conclusions, the ancient Egyptian scholars clung, as a rule, to the works of his predecessors.

Yet the earliest of times, it seems that the people of the Nile Valley sought out answers to make sense of the world around them. Gathering and storing food, selecting materials for shelters, making tools, struggling against disease and disorder were all concerns that would have led them to acquire and pass on a wide range of knowledge. This was of course not unique to the Egyptians and yet, the abundant resources of the Nile Valley may have, at an early stage, allowed them to ponder these issues without the extreme pressures of pure survival.

Nevertheless, it seems as though as soon as a body of knowledge had been accumulated which satisfied daily needs, it was regarded as sufficient, binding and largely immutable. If some serious incident or catastrophe occurred where accepted wisdom offered no help, the ancient Egyptian scholars, rather than trying to find out the reason, would turn to the writings to see how their predecessors would have coped with the situation. When they were forced to seek answers elsewhere, it was usually not through any doubt being cast on previous views but empirically, by checking the results given by current methods and coming up with alternative solutions that were better suited the the situation. Hence, it was the pressure of practical needs that sometimes forced the scribes to lay their scrolls aside and look for new approaches to new problems.

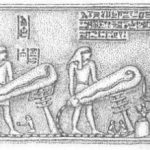

So it was that most of the inspiration for particular developments in Egyptian science was the need to solve a particular problem, such as the moving of large weights of stone, the calculation of the height or angles of pyramids, or predictions of the Nile inundation. Research appears not to have been undertaken for its own sake, and no attempt was made to derive general laws, such as mathematical theorems, from practical solutions.

As their social structure became more complex and developed, some tasks soon grew more specialized, so that only certain groups knew are used certain kinds of specialized information. However, it was probably not until Egypt was unified by a common king around 3,000 BC that Egyptian science began to really bloom. Indeed, it may very well have been this unification that spurred the development of writing at about the same time, and it was writing that gave Egypt the basis for scientific expansion. In fact, even the ancient Egyptians recognized this period as a golden era in science, the arts and technology.

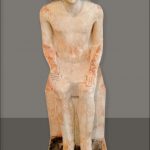

As early as the Old Kingdom, we find examples of historical scientific records including lists of annals. Theology and magic are represented by extensive collections such as the Pyramid Texts, and though we have only copies now, certainly some Wisdom Literature was originally written during the Old Kingdom.

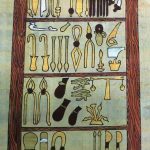

Just how specialized individual disciplines could be may best be understood when considering medicine. From tomb monuments we know that, for example, some specialized physicians existed. Herodotus writes that, “The practice of medicine is so divided among them that each physician treats one disease, and no more. There are plenty of physicians everywhere. Some are eye doctors, some deal with the head, others with the teeth or the belly, and some with hidden maladies…” . By the Middle Kingdom, we see more and more emerging sciences. Evidence, often in the form of lists, for example, document efforts to create an encyclopedic record of the world. In mathematics, there were good approximations for, and a method of calculating the surface and volumes of various geometric shapes. Astronomy began to be well documented, and of course, integrated into religion. This was also the beginning of the Bronze Age in Egypt, with its widespread adoption and use.