Ancient Egyptian literature comprises a wide array of narrative and poetic forms including inscriptions on tombs, stele, obelisks, and temples; myths, stories, and legends; religious writings; philosophical works; autobiographies; biographies; histories; poetry; hymns; personal essays; letters and court records. Although many of these forms are not usually defined as “literature” they are given that designation in Egyptian studies because so many of them, especially from the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE), are of such high literary merit.

The first examples of Egyptian writing come from the Early Dynastic Period (c. 6000- c. 3150 BCE) in the form of Offering Lists and autobiographies; the autobiography was carved on one’s tomb along with the Offering List to let the living know what gifts, and in what quantity, the deceased was due regularly in visiting the grave. Since the dead were thought to live on after their bodies had failed, regular offerings at graves were an important consideration; the dead still had to eat and drink even if they no longer held a physical form. From the Offering List came the Prayer for Offerings, a standard literary work which would replace the Offering List, and from the autobiographies grew the Pyramid Texts which were accounts of a king’s reign and his successful journey to the afterlife; both these developments took place during the period of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-c.2181 BCE).

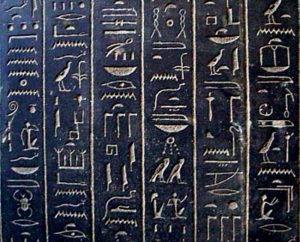

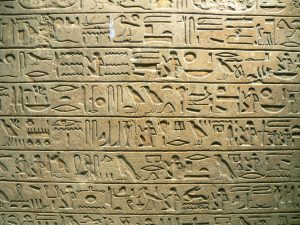

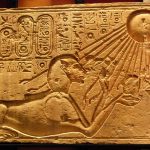

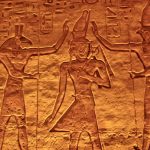

These texts were written in hieroglyphics (“sacred carvings”) a writing system combining phonograms (symbols which represent sound), logograms (symbols representing words), and ideograms (symbols which represent meaning or sense). Hieroglyphic writing was extremely labor intensive and so another script grew up beside it known as hieratic (“sacred writings”) which was faster to work with and easier to use. Hieratic was based on hieroglyphic script and relied on the same principles but was less formal and precise. Hieroglyphic script was written with particular care for the aesthetic beauty of the arrangement of the symbols; hieratic script was used to relay information quickly and easily. In c. 700 BCE hieratic was replaced by demotic script (“popular writing”) which continued in use until the rise of Christianity in Egypt and the adoption of Coptic script c. 4th century CE.

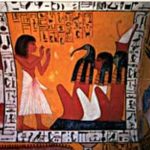

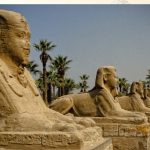

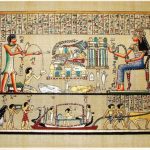

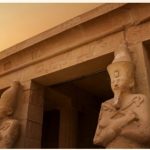

Most of Egyptian literature was written in hieroglyphics or hieratic script; hieroglyphics were used on monuments such as tombs, obelisks, stele, and temples while hieratic script was used in writing on papyrus scrolls and ceramic pots. Although hieratic, and later demotic and Coptic, scripts became the common writing system of the educated and literate, hieroglyphics remained in use throughout Egypt’s history for monumental structures until it was forgotten during the early Christian period.

Although the definition of “Egyptian Literature” includes many different types of writing, for the present purposes attention will mostly be paid to standard literary works such as stories, legends, myths, and personal essays; other kinds or work will be mentioned when they are particularly significant. Egyptian history, and so literature, spans centuries and fills volumes of books; a single article cannot hope to treat of the subject fairly in attempting to cover the wide range of written works of the culture.

Literature in the Old Kingdom

The Offering Lists and autobiographies, though not considered “literature”, are the first examples of the Egyptian writing system in action. The Offering List was a simple instruction, known to the Egyptians as the hetep-di-nesw (“a boon given by the king”), inscribed on a tomb detailing food, drink, and other offerings appropriate for the person buried there. The autobiography, written after the person’s death, was always inscribed in the first person as though the deceased were speaking. Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim writes:

The basic aim of the autobiography – the self-portrait in words – was the same as that of the self-portrait in sculpture and relief: to sum up the characteristic features of the individual person in terms of his positive worth and in the face of eternity. (4)

These early obituaries came to be augmented by a type of formulaic writing now known as the Catalogue of Virtues which grew from “the new ability to capture the formless experiences of life in the enduring formulations of the written word” (Lichtheim, 5). The Catalogue of Virtues accentuated the good a person had done in his or her life and how worthy they were of remembrance. Lichtheim notes that the importance of the Virtues was that they “reflected the ethical standards of society” while at the same time making clear that the deceased had adhered to those standards (5). Some of these autobiographies and lists of virtues were brief, inscribed on a false door or around the lintels; others, such as the well-known Autobiography of Weni, were inscribed on large monolithic slabs and were quite detailed. The autobiography was written in prose; the Catalogue in formulaic poetry. A typical example of this is seen in the Inscription of Nefer-Seshem-Ra Called Sheshi from the 6th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom:

I have come from my town

I have descended from my nome

I have done justice for its lord

I have satisfied him with what he loves.

I spoke truly, I did right

I spoke fairly, I repeated fairly

I seized the right moment

So as to stand well with people.

I judged between two so as to content them

I rescued the weak from the stronger than he

As much as was in my power.

I gave bread to the hungry, clothes to the naked

I brought the boatless to land.

I buried him who had no son,

I made a boat for him who lacked one.

I respected my father, I pleased my mother,

I raised their children.

So says he whose nickname is Sheshi. (Lichtheim, 17)

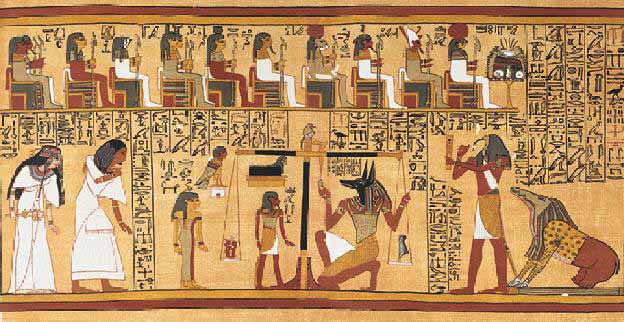

These autobiographies and virtue lists gave rise to the Pyramid Texts of the 5th and 6th dynasties which were reserved for royalty and told the story of a king’s life, his virtues, and his journey to the afterlife; they therefore tried to encompass the earthly life of the deceased and his immortal journey on into the land of the gods and, in doing so, recorded early religious beliefs. Creation myths such as the famous story of Atum standing on the primordial mound amidst the swirling waters of chaos, weaving creation from nothing, comes from the Pyramid Texts. These inscriptions also include allusions to the story of Osiris, his murder by his brother Set, his resurrection from the dead by his sister-wife Isis, and her care for their son Horus in the marshes of the Delta.

Following closely on the heels of the Pyramid Texts, a body of literature known as the Instructions in Wisdom appeared. These works offer short maxims on how to live much along the lines of the biblical Book of Proverbs and, in many instances, anticipate the same kinds of advice one finds in Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Psalms, and other biblical narratives. The oldest Instruction is that of Prince Hardjedef written sometime in the 5th Dynasty which includes advice such as:

Cleanse yourself before your own eyes

Lest another cleanse you.

When you prosper, found your household,

Take a hearty wife, a son will be born to you.

It is for the son you build a house

When you make a place for yourself. (Lichtheim, 58)

The somewhat later Instruction Addressed to Kagemni advises:

The respectful man prospers,

Praised is the modest one.

The tent is open to the silent,

The seat of the quiet is spacious

Do not chatter!…

When you sit with company,

Shun the food you love;

Restraint is a brief moment

Gluttony is base and is reproved.

A cup of water quenches the thirst,

A mouthful of herbs strengthens the heart. (Lichtheim, 59-60)

There were a number of such texts, all written according to the model of Mesopotamian Naru Literature, in which the work is ascribed to, or prominently features, a famous figure. The actual Prince Hardjedef did not write his Instruction nor was Kagemni’s addressed to the actual Kagemni. As in Naru literature, a well-known person was chosen to give the material more weight and so wider acceptance. Wisdom Literature, the Pyramid Texts, and the autobiographical inscriptions developed significantly during the Old Kingdom and became the foundation for the literature of the Middle Kingdom.